Sustainable Food Estates

Implementation, impacts and opportunities

Sustainable Food Estates

Implementation, impacts and opportunities

December 1, 2025

LEAF Indonesia, funded by the Global Centre on Biodiversity for Climate (GCBC), is a transdisciplinary research partnership between the University of Sussex, Monash University, Universitas Negeri Gorontalo, Universitas Papua, and Universitas Mulawarman.

You are viewing a Storymap which introduces the results of our first phase of work with Indonesian farming communities, government agencies, NGOs, and conservation organizations to find ways to balance Indonesia’s food security goals with environmental protection, climate resilience, and the well-being of local communities.

Scroll down to reveal the story. You can navigate to any part of the story using the dropdown table of contents at the top right of the screen.

Introduction

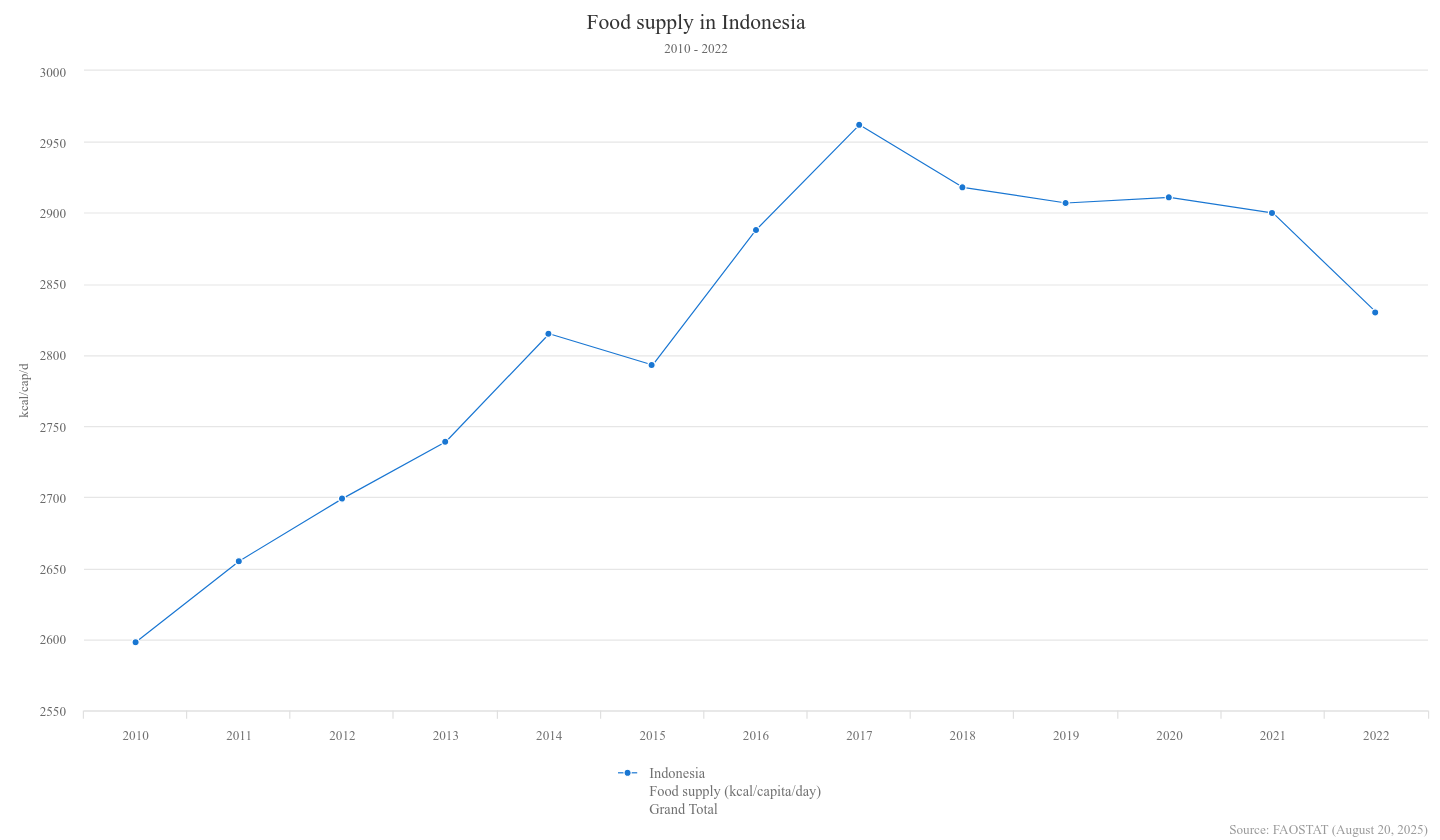

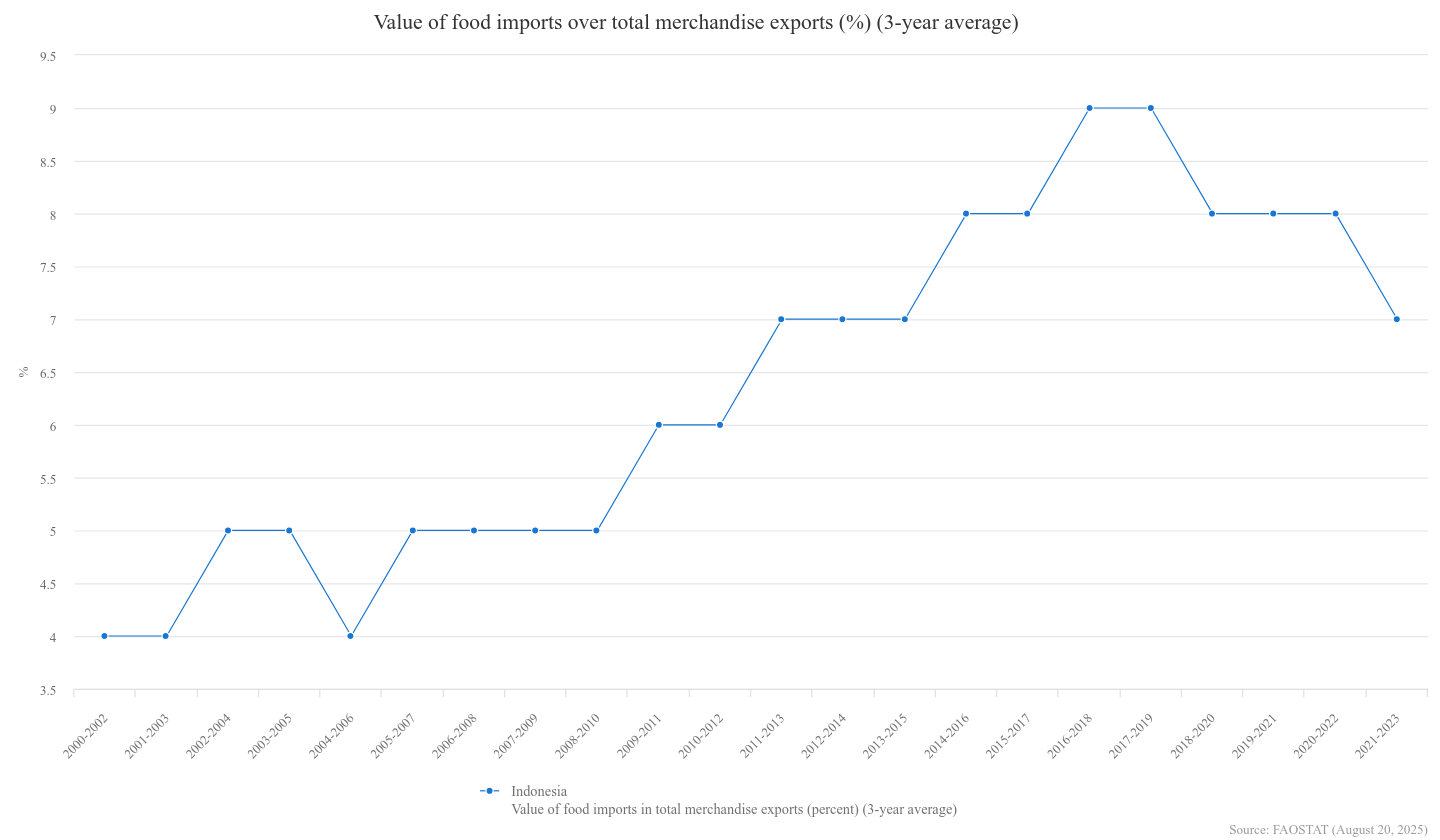

In April 2020, four months into the COVID-19 pandemic, the World Food Programme published a report outlining the likely food security implications of the unfolding crisis due to the disruption of global trade, humanitarian actions, and food production, as well as impacts on health and poverty for millions of the world’s poorest.

Partly in reaction to this report, in June 2020, Indonesia’s President Jokowi announced plans for an expansion of the Food Estate Program to ensure Indonesia’s future food self-sufficiency.

Led by then-defence Minister Prabowo, the program was intended to convert four million hectares of land for food production by 2029, thereby increasing rice production by 10 million tons annually and, ultimately, achieving rice self-sufficiency.

How could this be done in a way that genuinely improves food security for Indonesians, especially the poorest? And what would such a massive change in land-use mean for biodiversity, climate change and livelihoods?

What would it mean for one of the world’s largest, most populous and most biodiverse countries to transform its national food system from a mosaic of smallholder farms and export oriented commercial plantations into a self-sufficient modernized agricultural powerhouse?

To begin to answer this question we will take you through an overview of Indonesia’s food security challenge and tell you the story of how the food estate idea came to take on such a central role in Indonesian policy. Finally, we will introduce you to the three provinces where we are working with rural communities to understand the impacts of food estates on biodiversity, climate resilience and livelihoods and to try to imagine a more sustainable model for food estates into the future.

The Challenge of Feeding an Archipelago

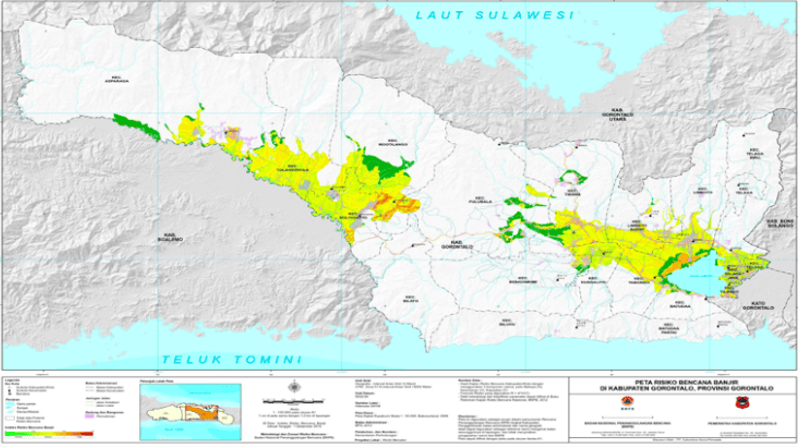

Indonesia’s challenge to feed its vast archipelago is shaped by a convergence of environmental pressures, livelihood strains, land dilemmas, and governance gaps. On the environmental front, the country faces increasing floods, droughts, and forest fires that disrupt farming cycles and destroy harvests. Deforestation for plantations reduces arable land and alters rainfall, while soil degradation lowers productivity and biodiversity loss undermines resilience against pests and climate shocks. These ecological stresses weaken the very foundations of food production.

Impacts of land-use change on competition for farmland

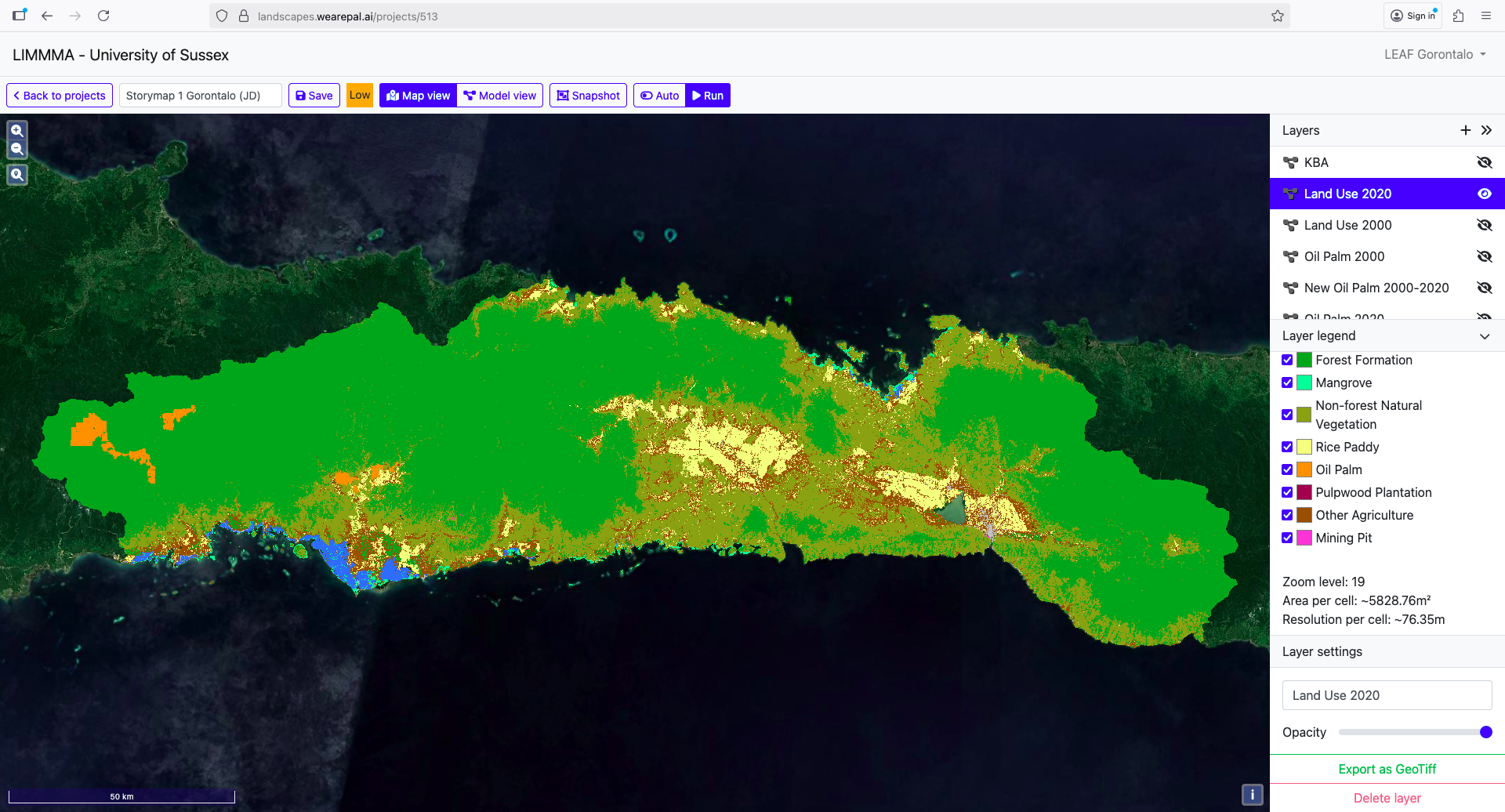

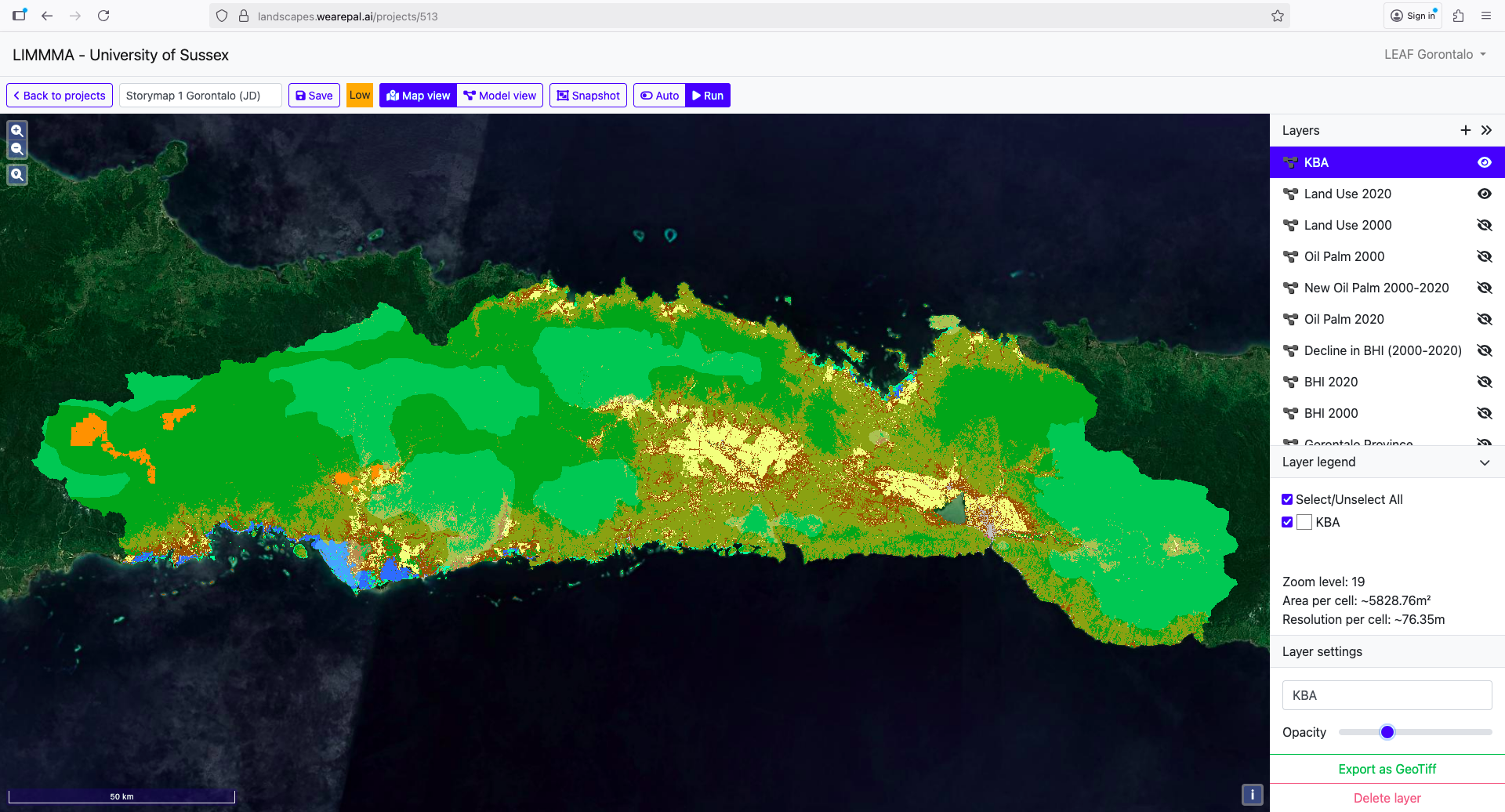

Now let’s see how land-use has changed over time.

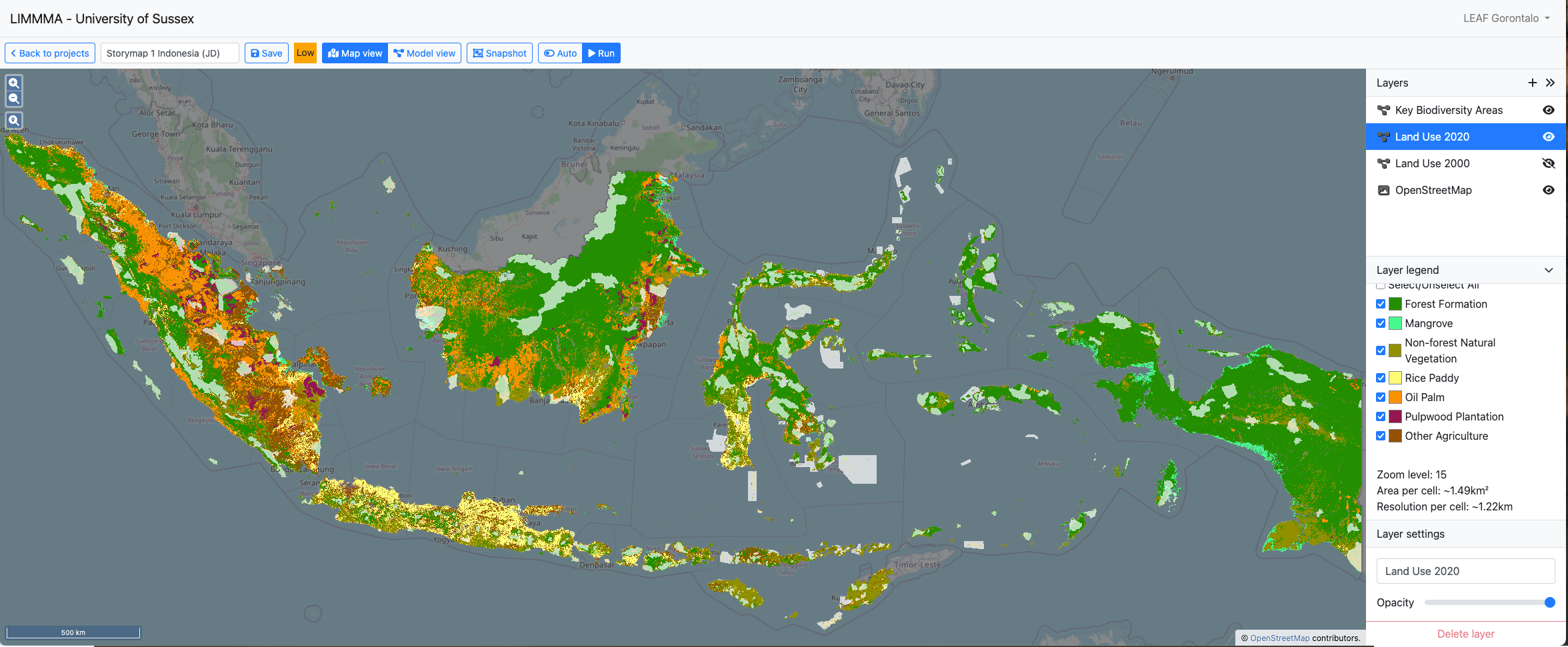

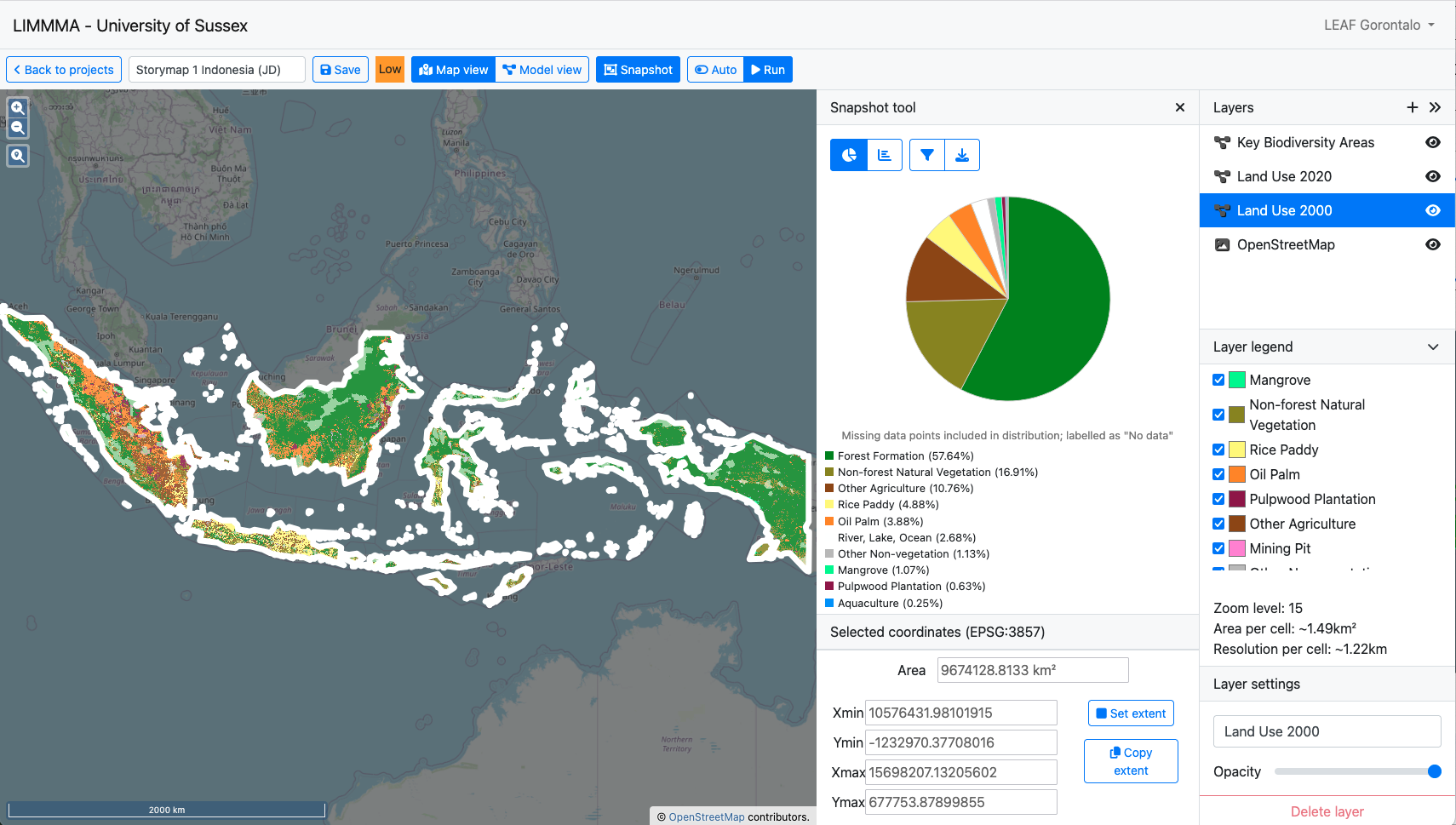

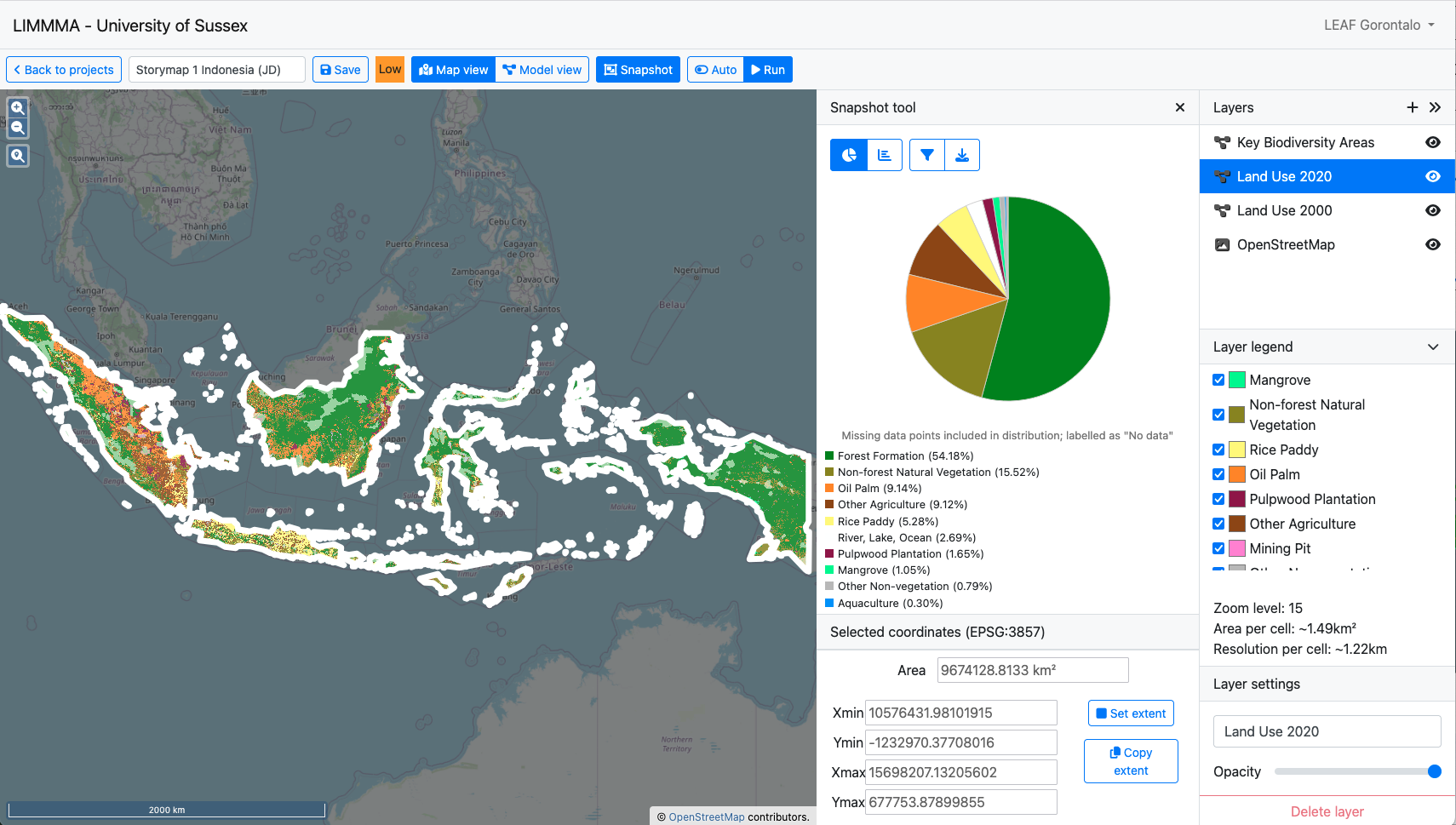

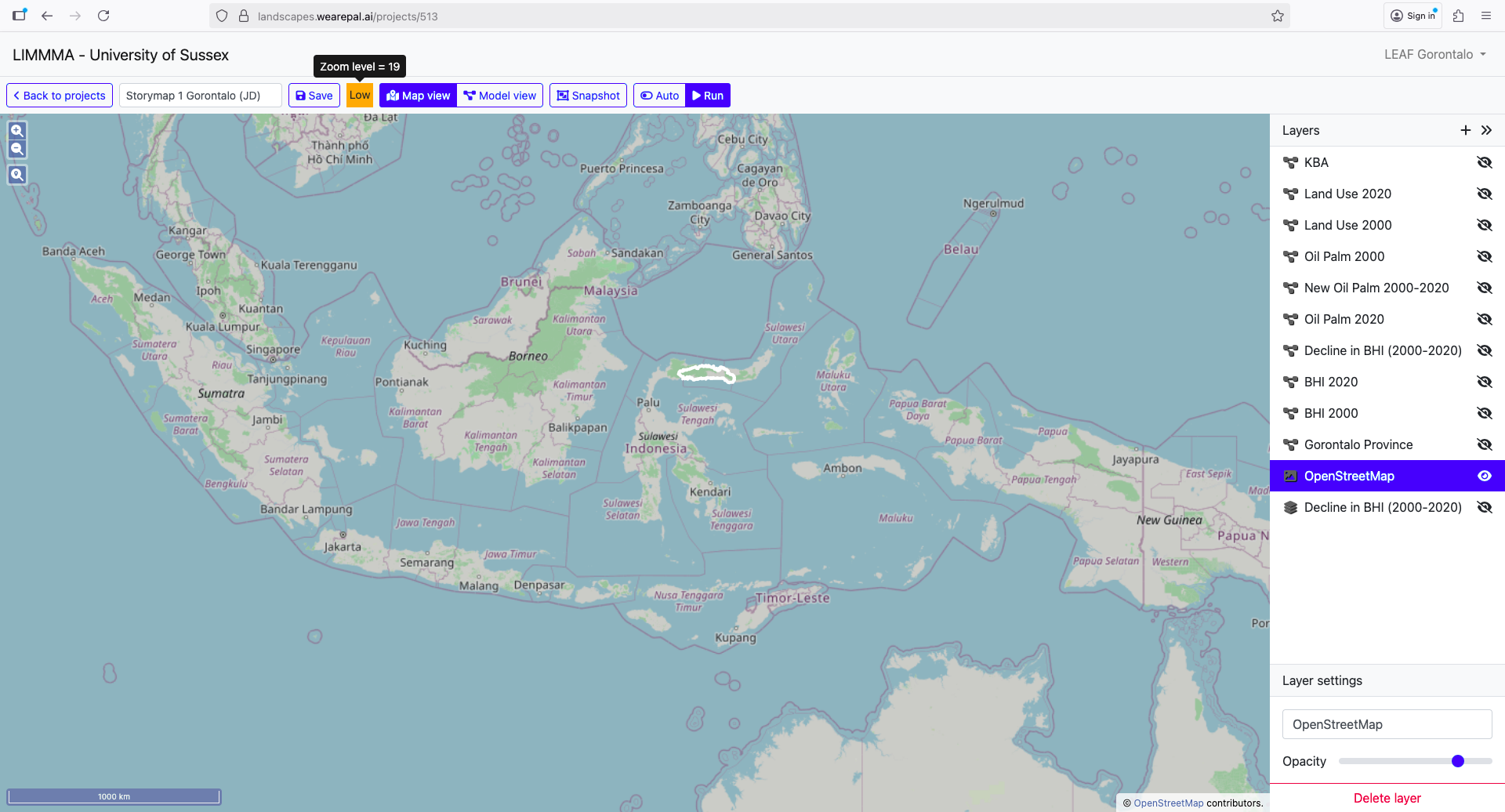

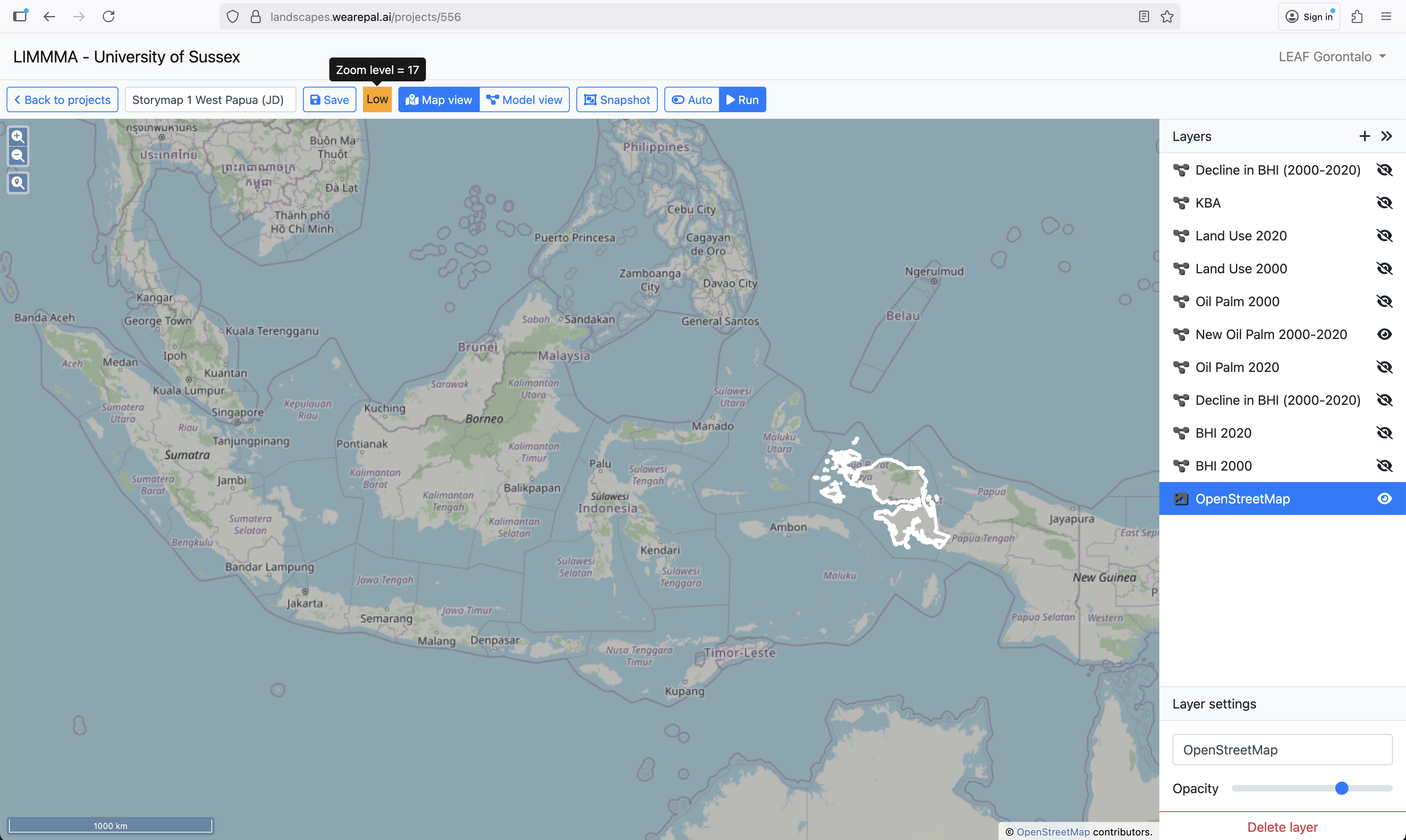

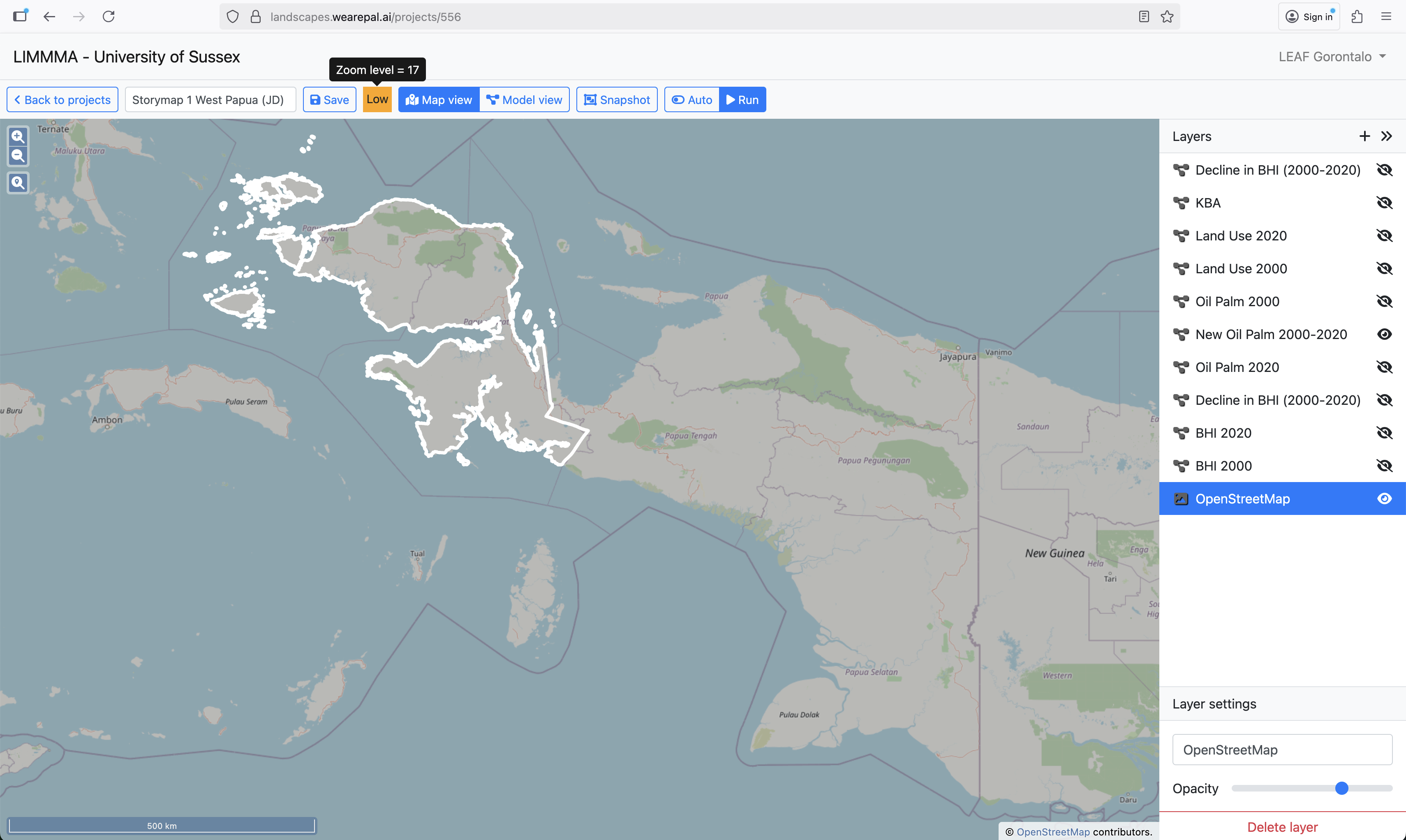

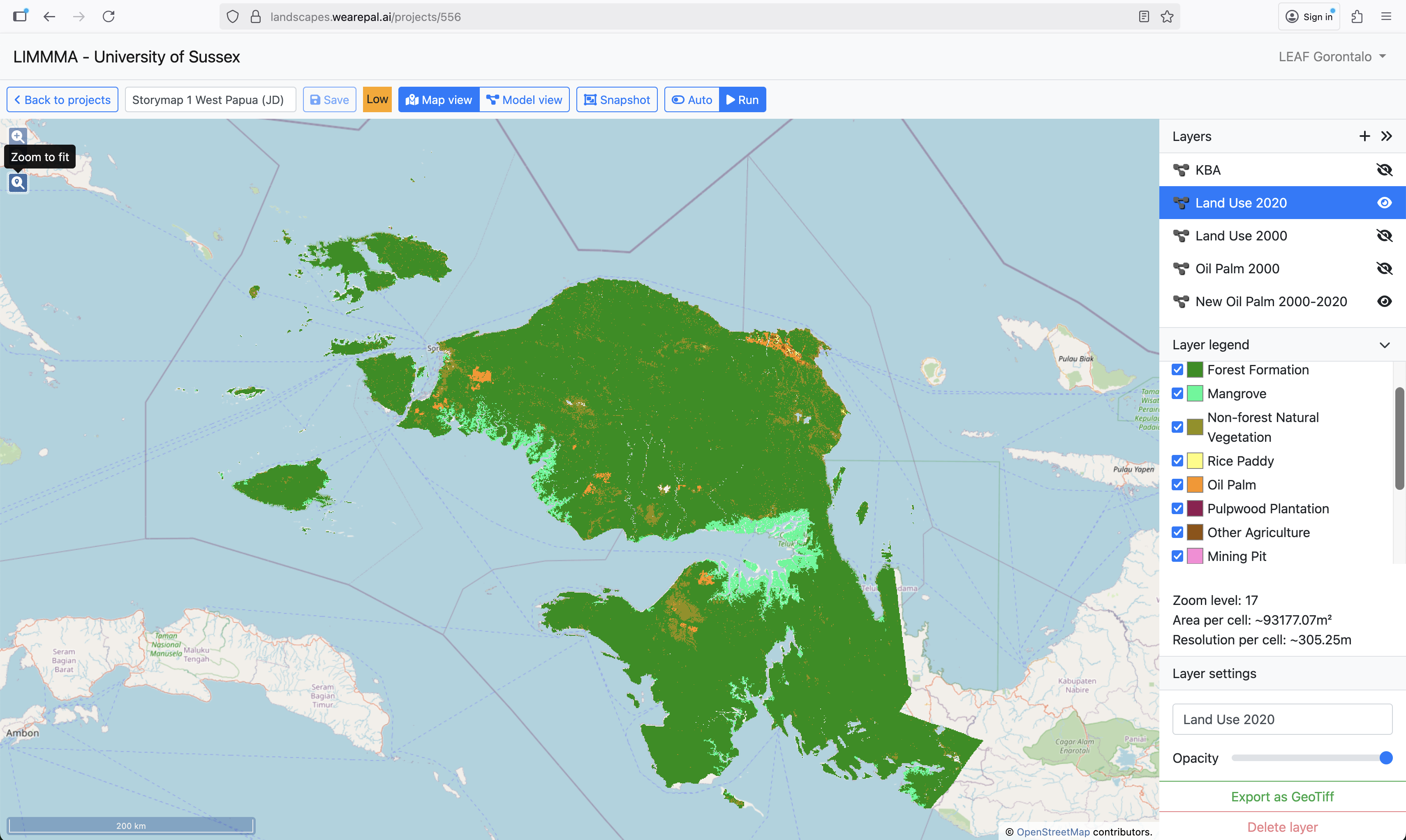

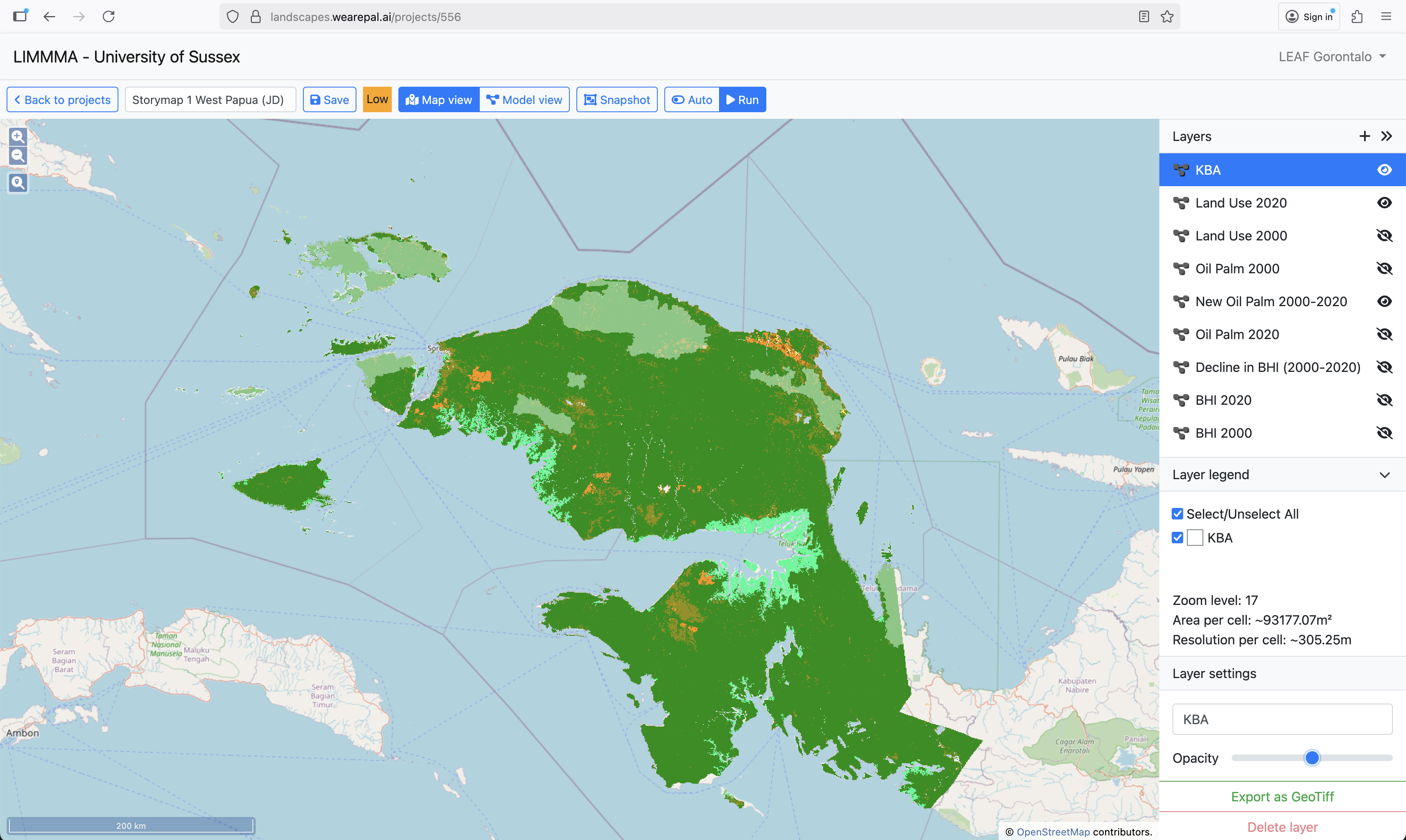

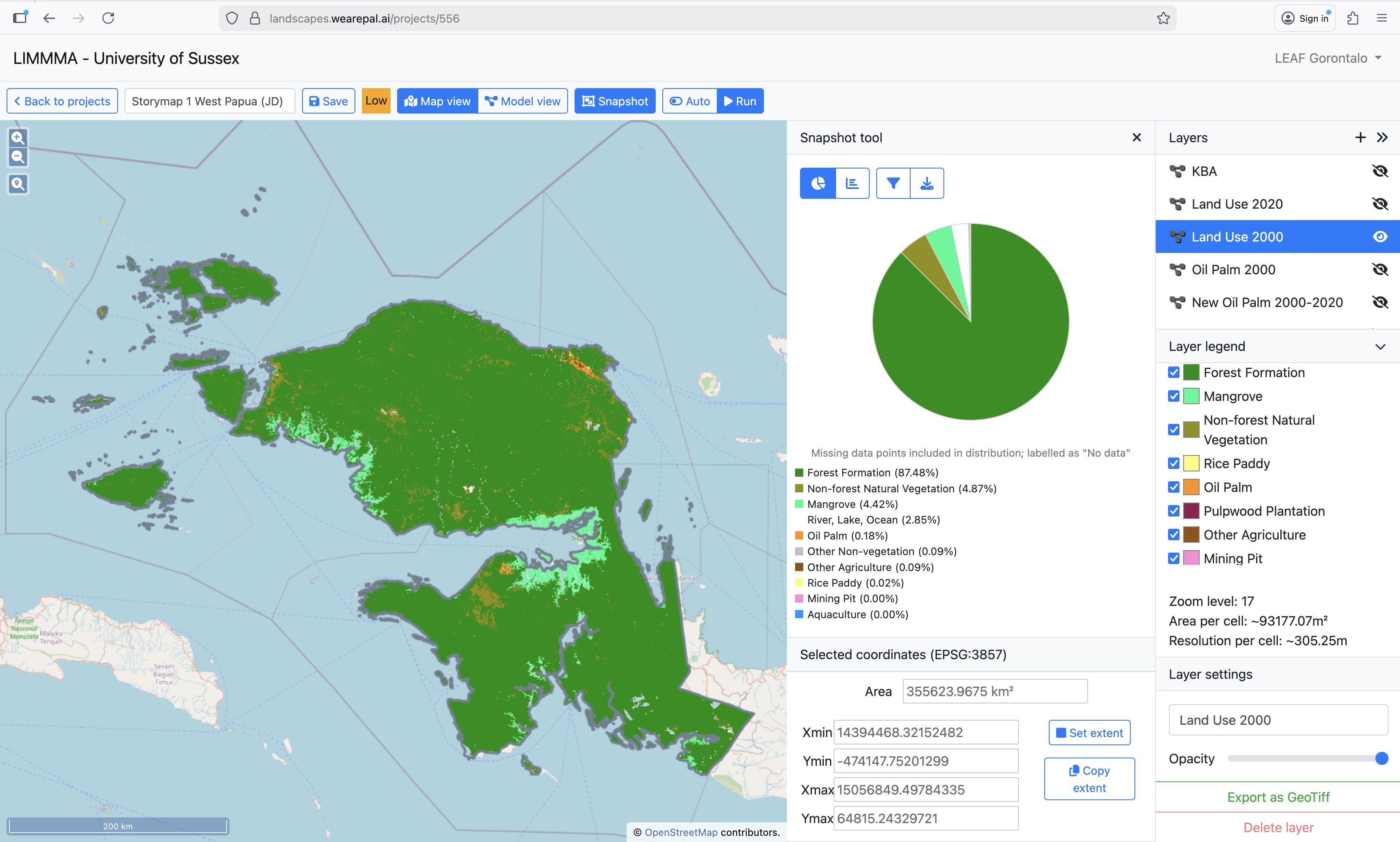

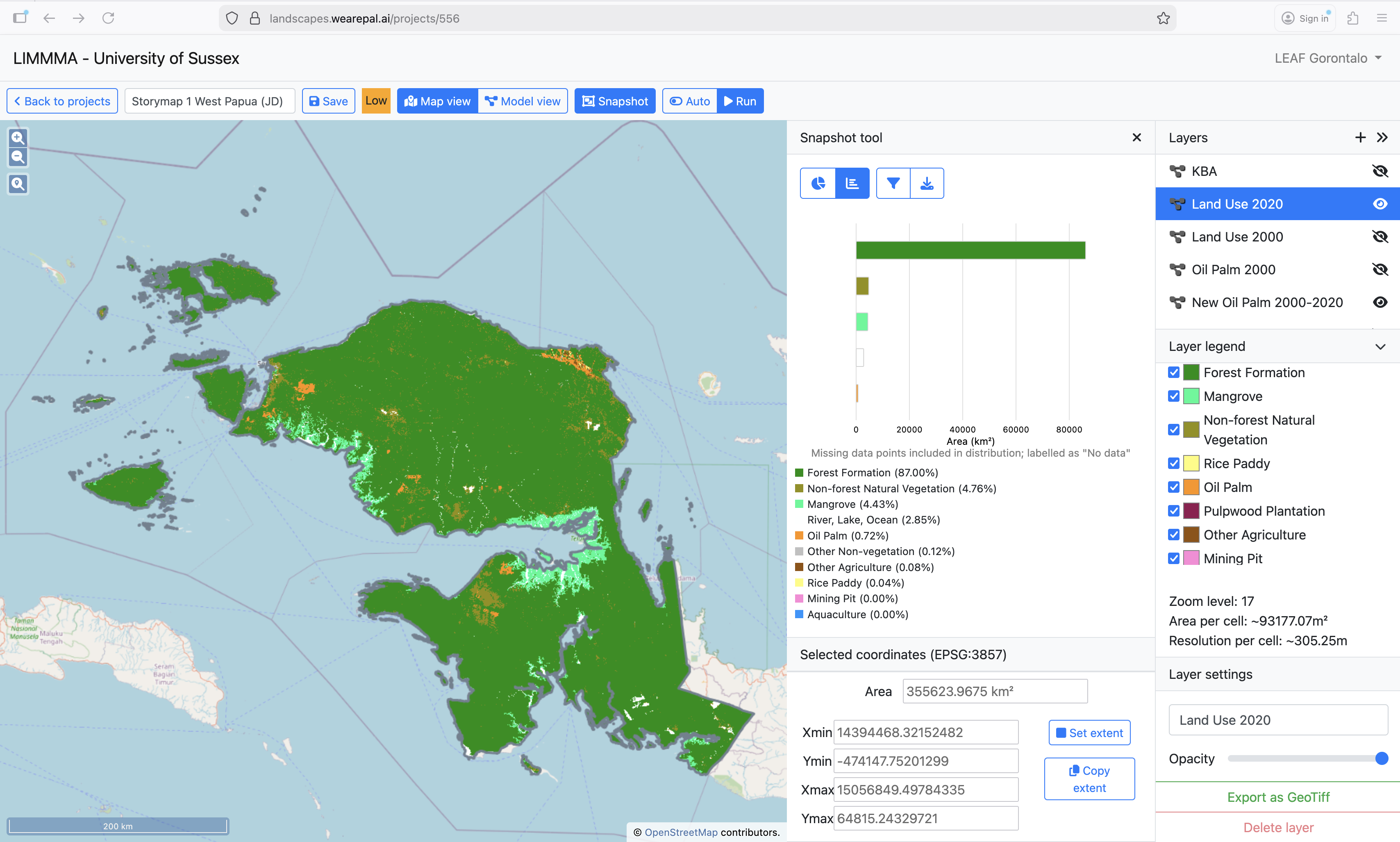

Below is a map of land-use in Indonesia from LIMMMA.

Move the slider from right to left to observe how land-use has changed between 2000 (left-hand image) and 2020 (right-hand image).

Notice the expansion of Oil Palm (orange colour) and Pulpwood plantation (in maroon colour) across Kalimantan and Sumatra.

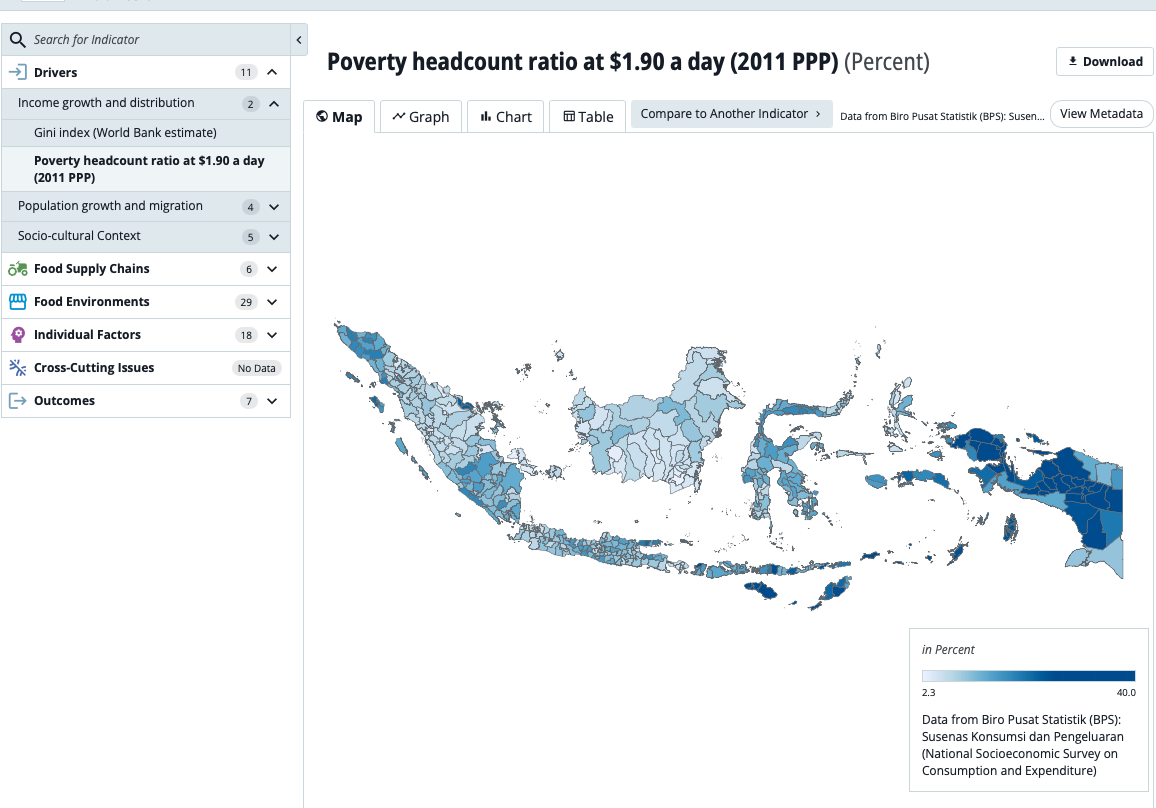

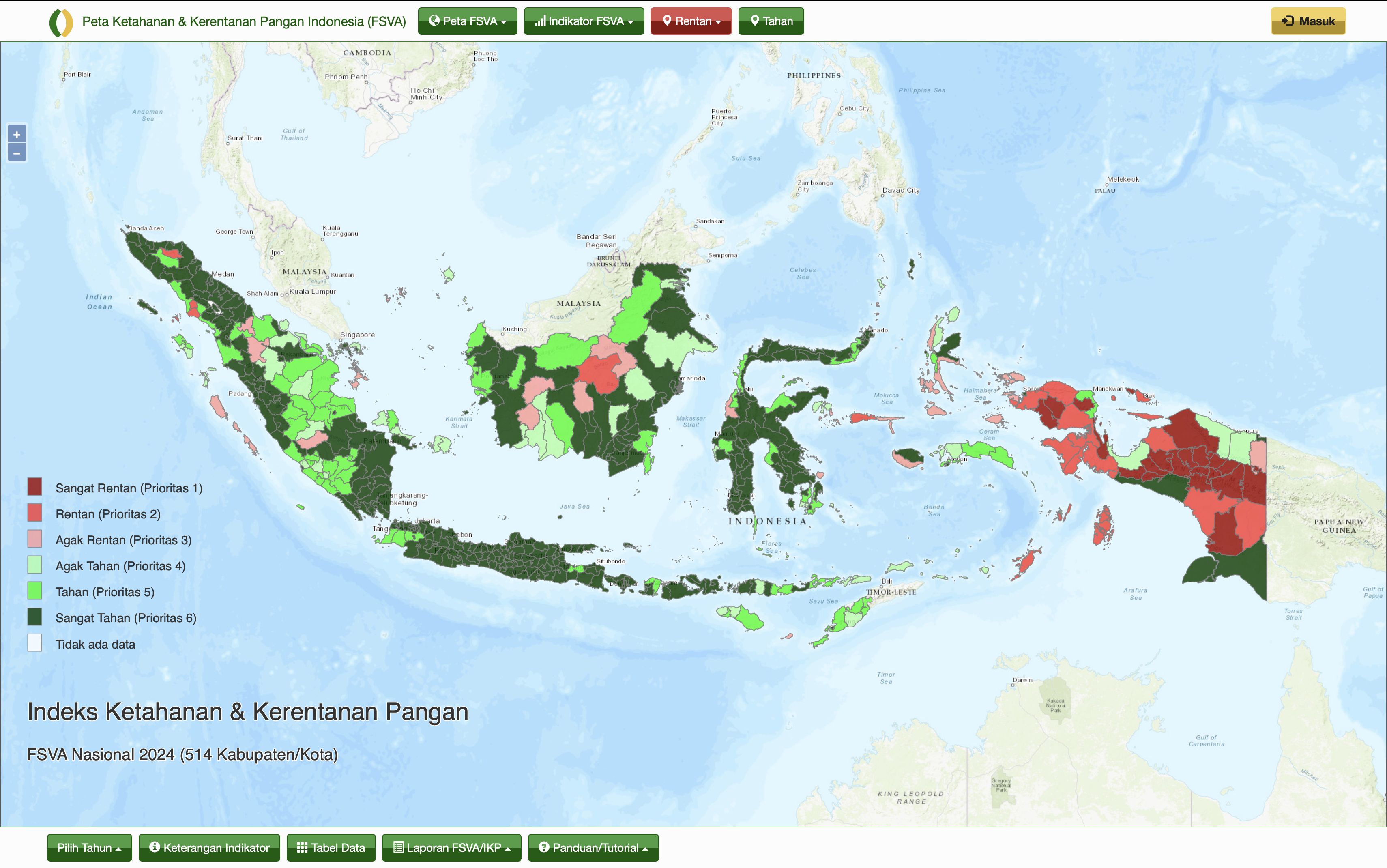

While land for food crops is under pressure from plantations and other source of land-use change, farming communities also experience mounting livelihood strains. Local famines, especially in eastern Indonesia, reveal persistent vulnerabilities in food access. Farmers struggle with unstable prices, high costs, and limited market access, while younger generations are leaving agriculture due to low returns and limited innovation. This farmer regeneration crisis, coupled with slow adoption of technology and knowledge, leaves rural livelihoods fragile and food systems less resilient.

Underlying these pressures on food security and livelihoods are land and governance challenges. Land expansion for commodity crops reduces space for food farming, while fragmentation of farmland into smaller plots limits efficiency and long-term investment. Indonesia’s diverse geography adds further stress, with mountainous terrain, drought-prone regions, and rising sea levels shaping uneven agricultural viability. On the governance side, centralized and top-down approaches often impose uniform policies that fail to reflect local realities. Limited use of research evidence slows the uptake of climate-smart practices, and the exclusion of women, indigenous peoples, and marginalized groups deepens inequality.

Taken together, these interlinked crises form a cycle in which environmental decline worsens rural hardship, and livelihood strains drive unsustainable practices that further degrade ecosystems. Breaking this cycle requires solutions that link the natural and social dimensions of food security: climate-smart farming and agroecology, farmer regeneration and youth programs, land reform and better spatial planning, and more inclusive, evidence-based governance.

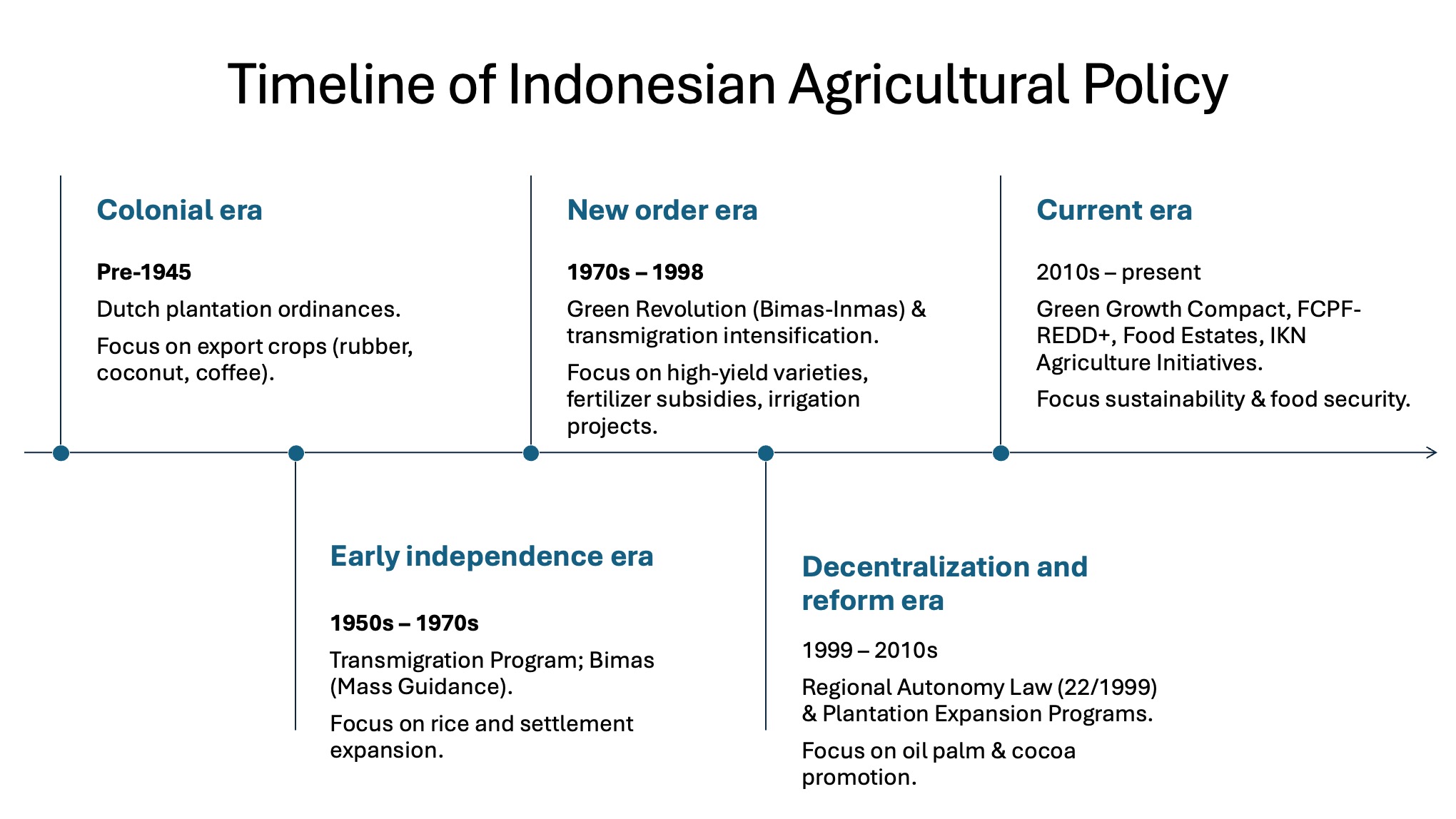

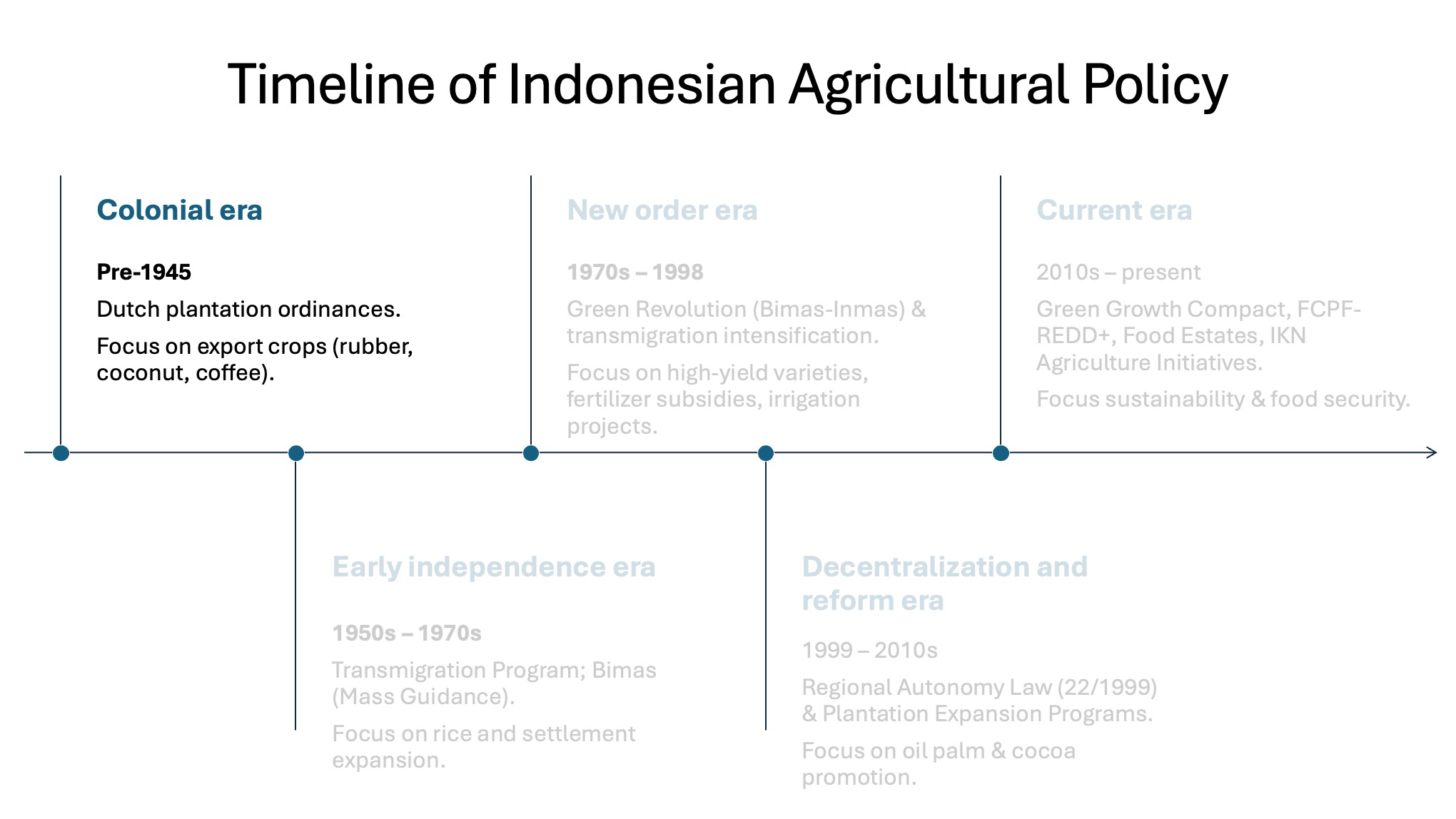

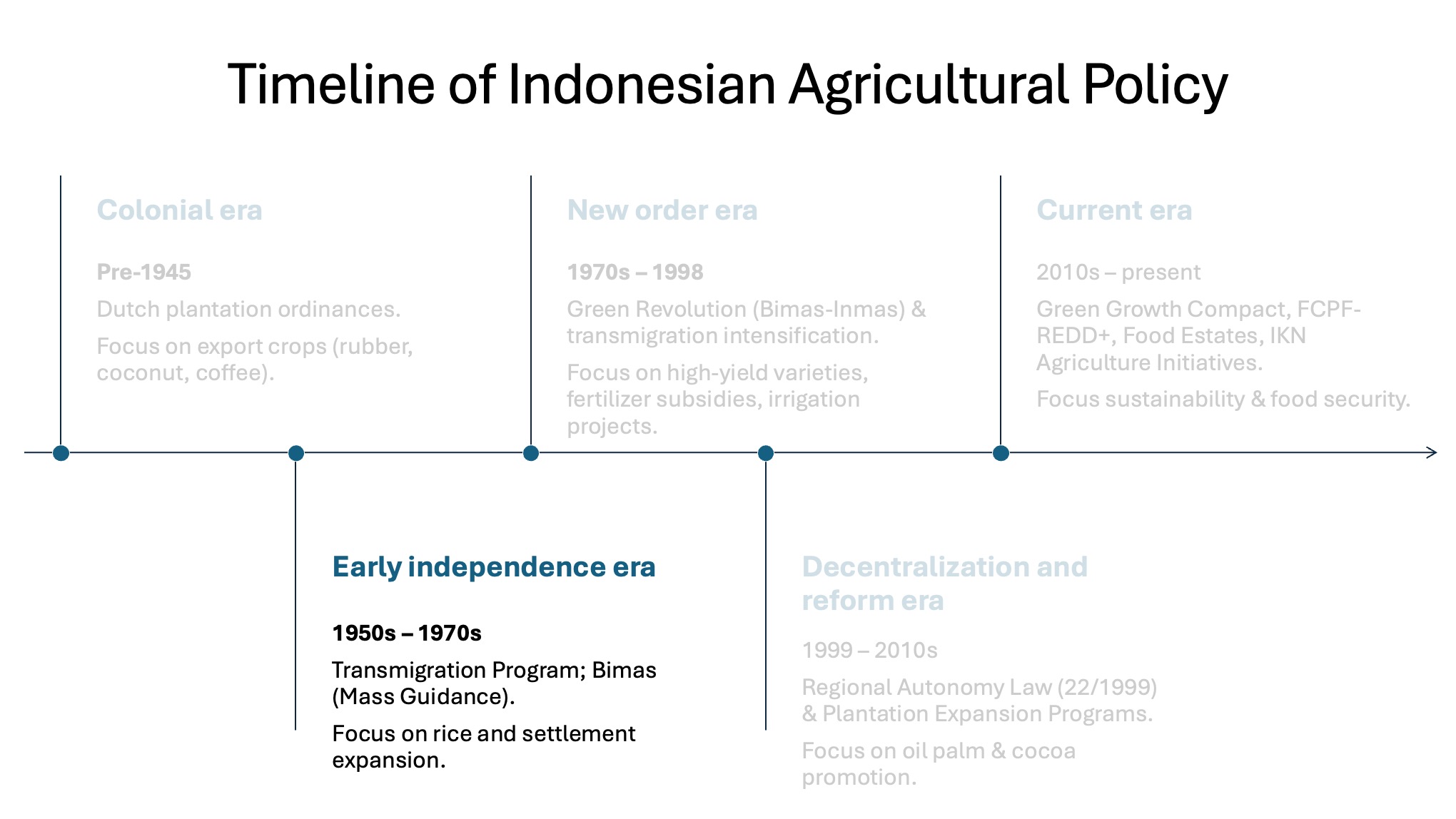

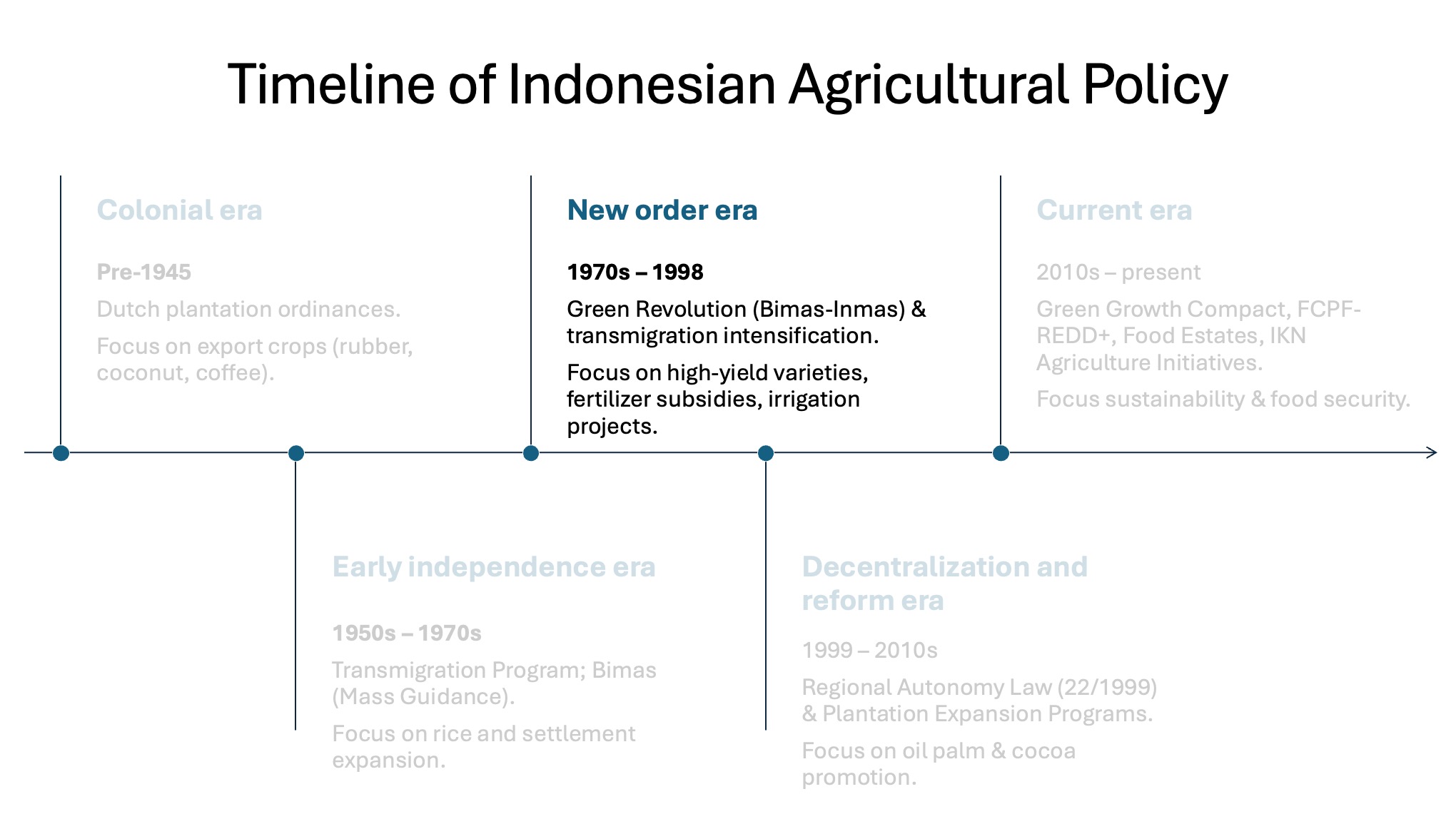

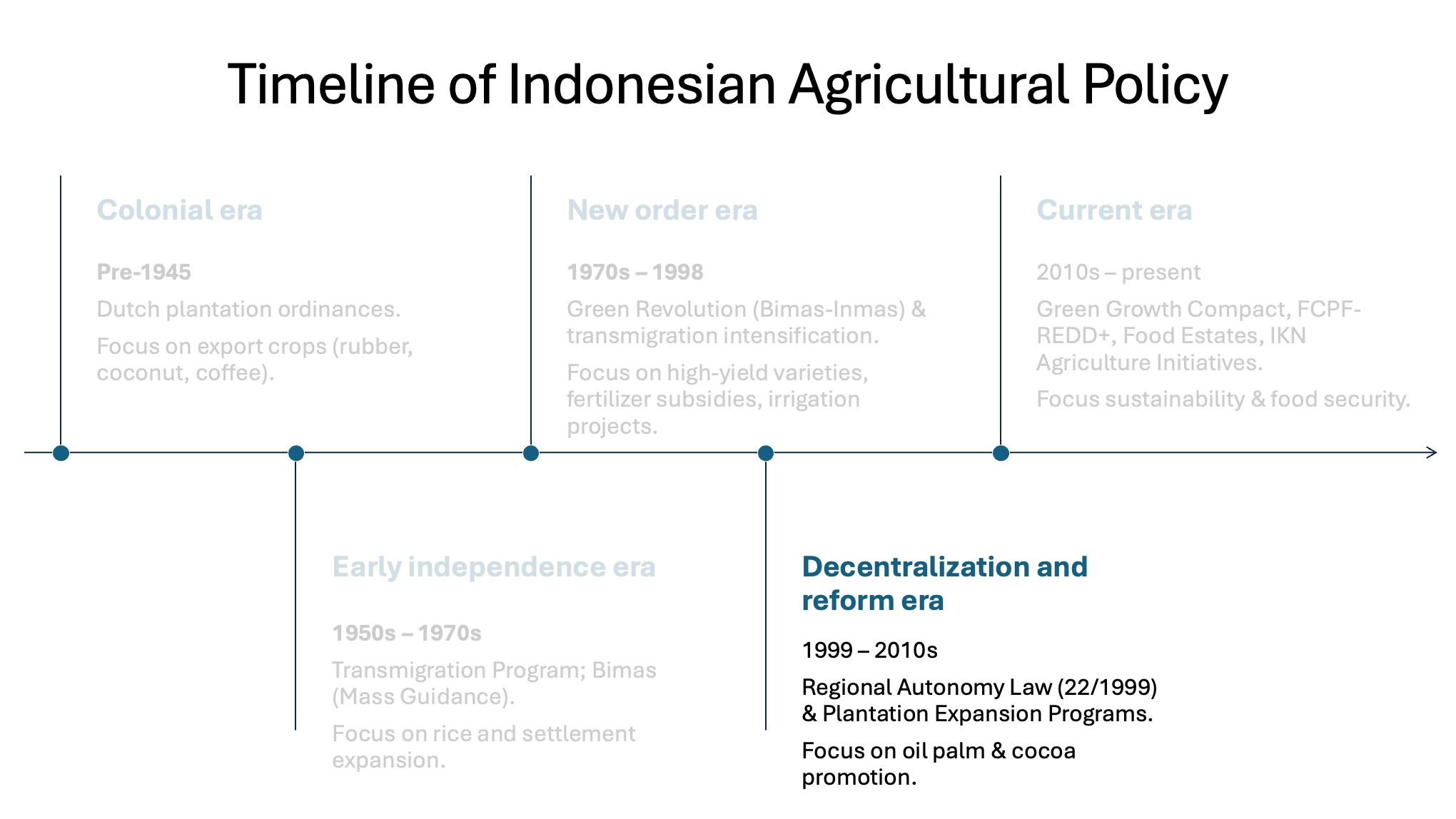

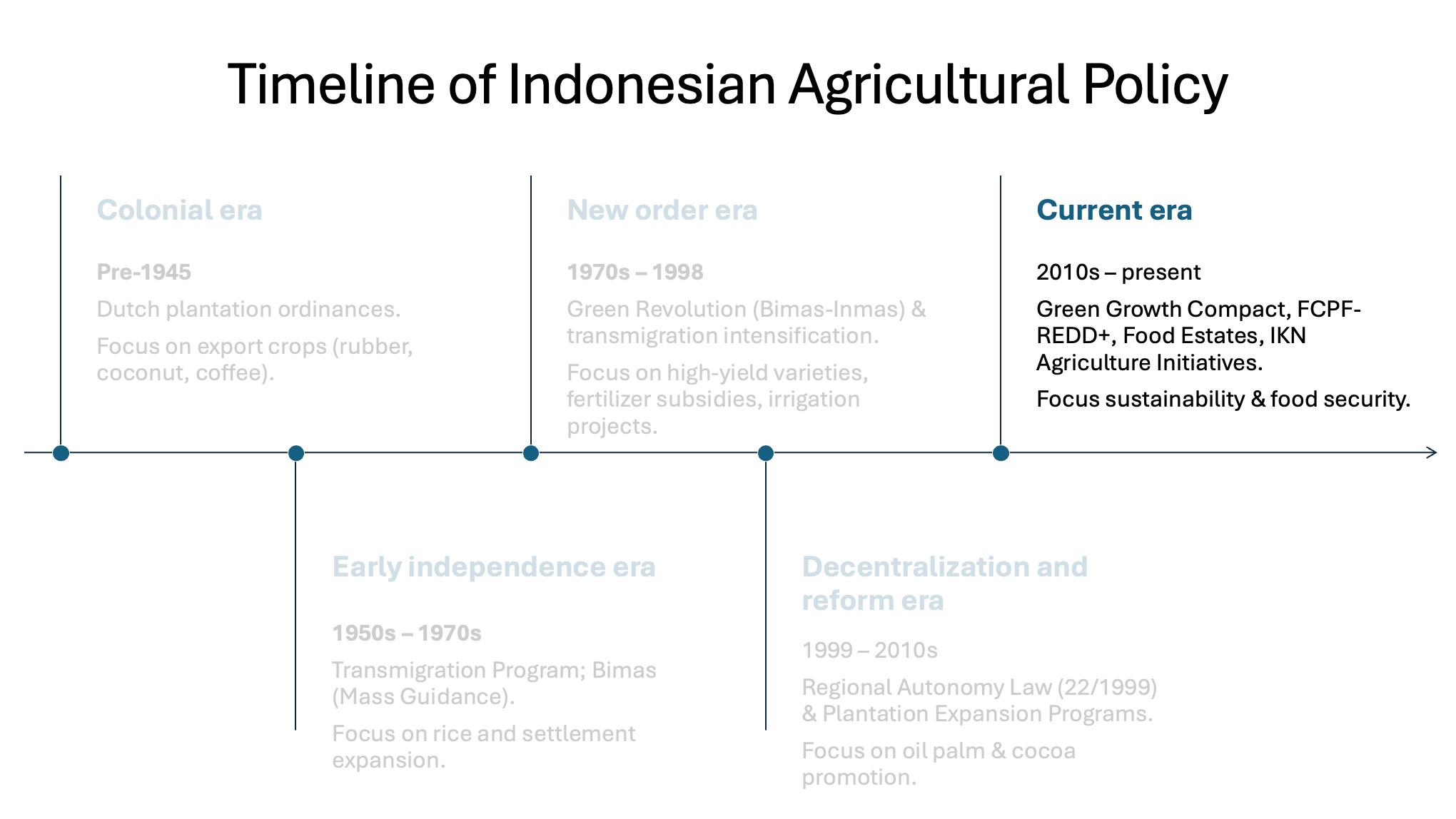

Origins and evolution of food estates

These patterns of land-use are the result of the complex interaction of changing policies, legal frameworks, global and national markets, and local socio-economic trends.

Food estates in local context

Having described Indonesia’s food security challenge and the covered the historical context of food estates in Indonesia we now want to introduce you to the three provinces in which we are working.

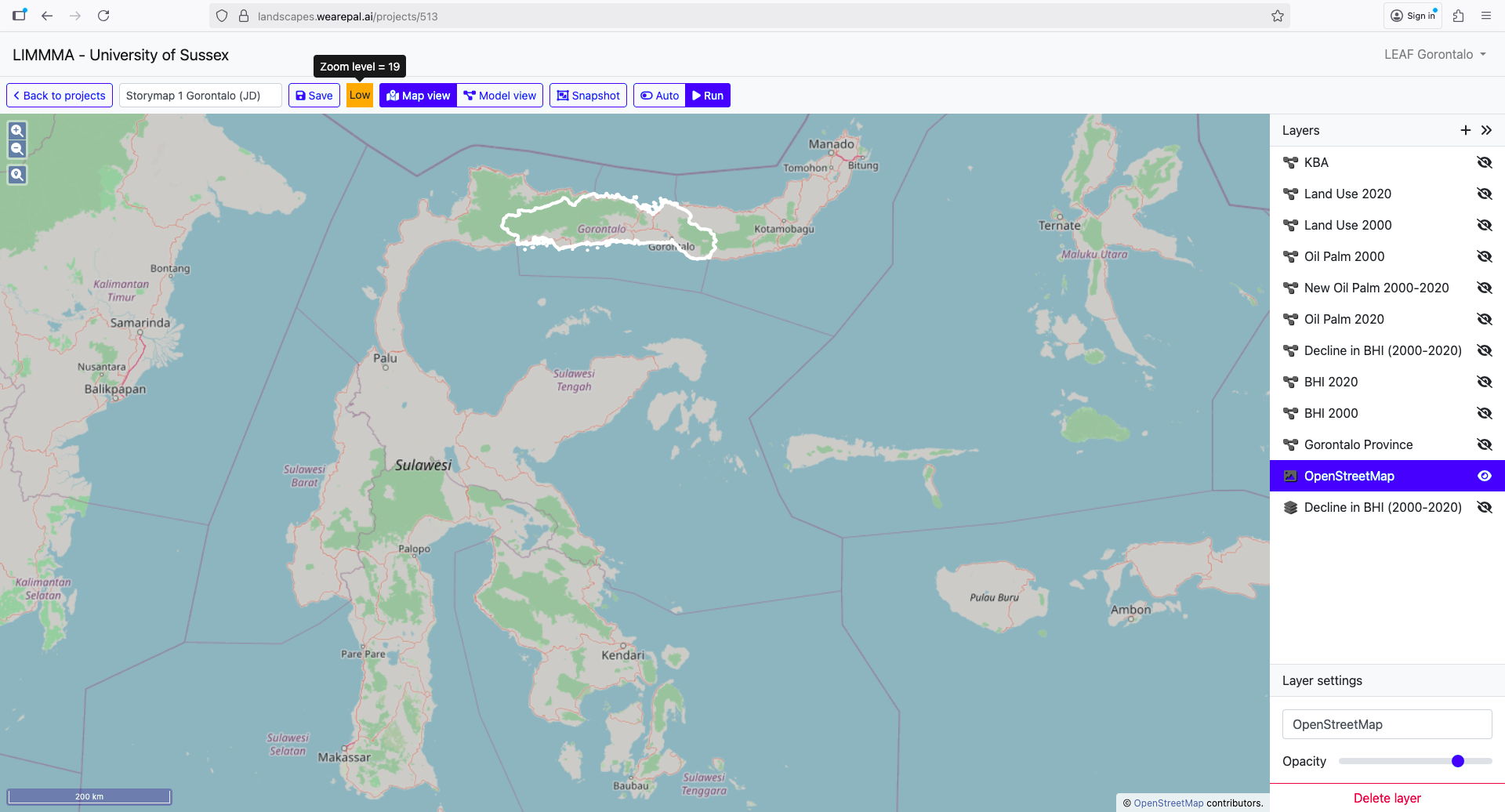

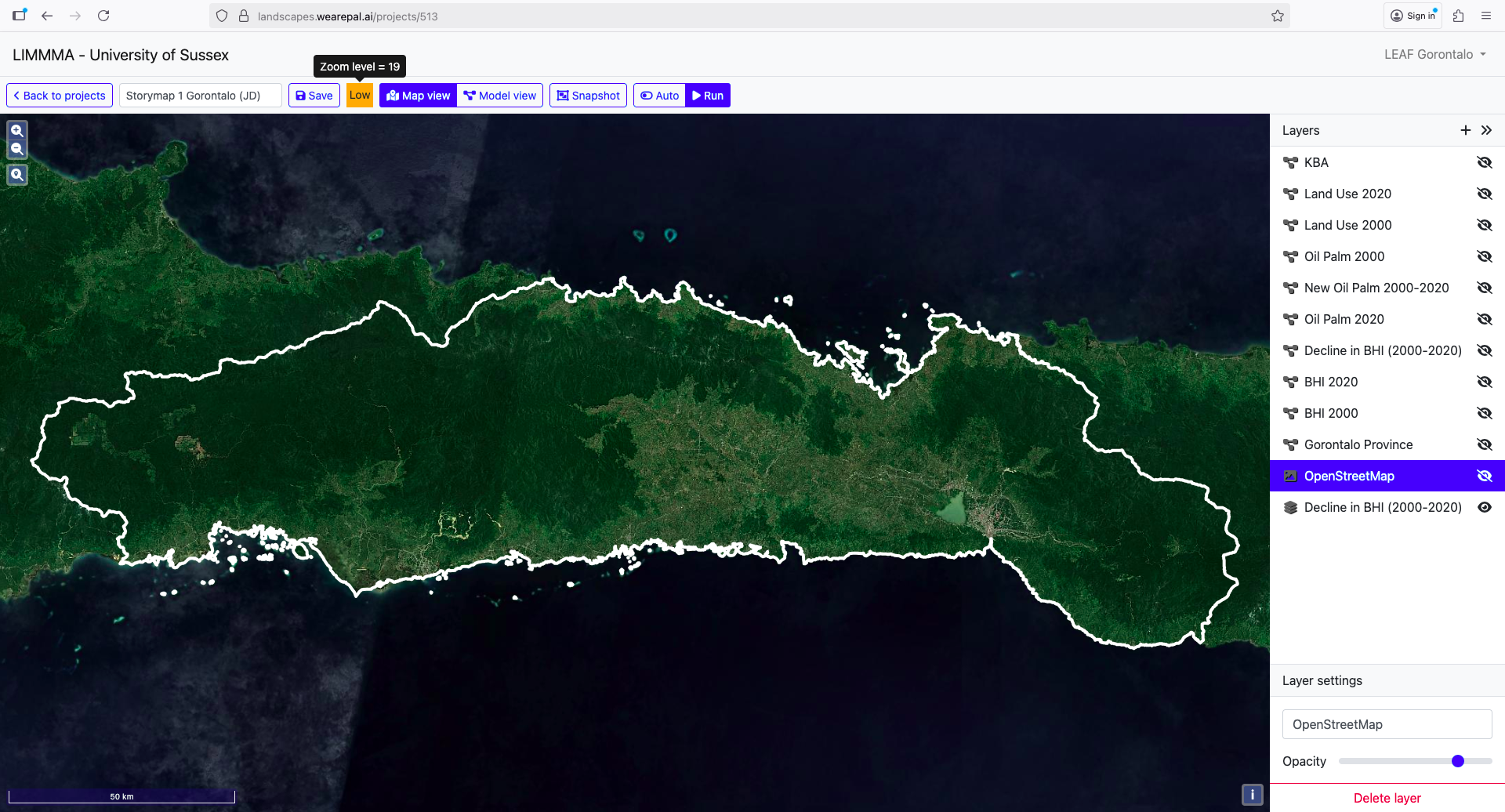

Gorontalo

Bogani National Park is spans across Gorontalo Province and North Sulawesi and is a vital source of fresh water resources for downstream communities.

Agricultural in Gorontalo

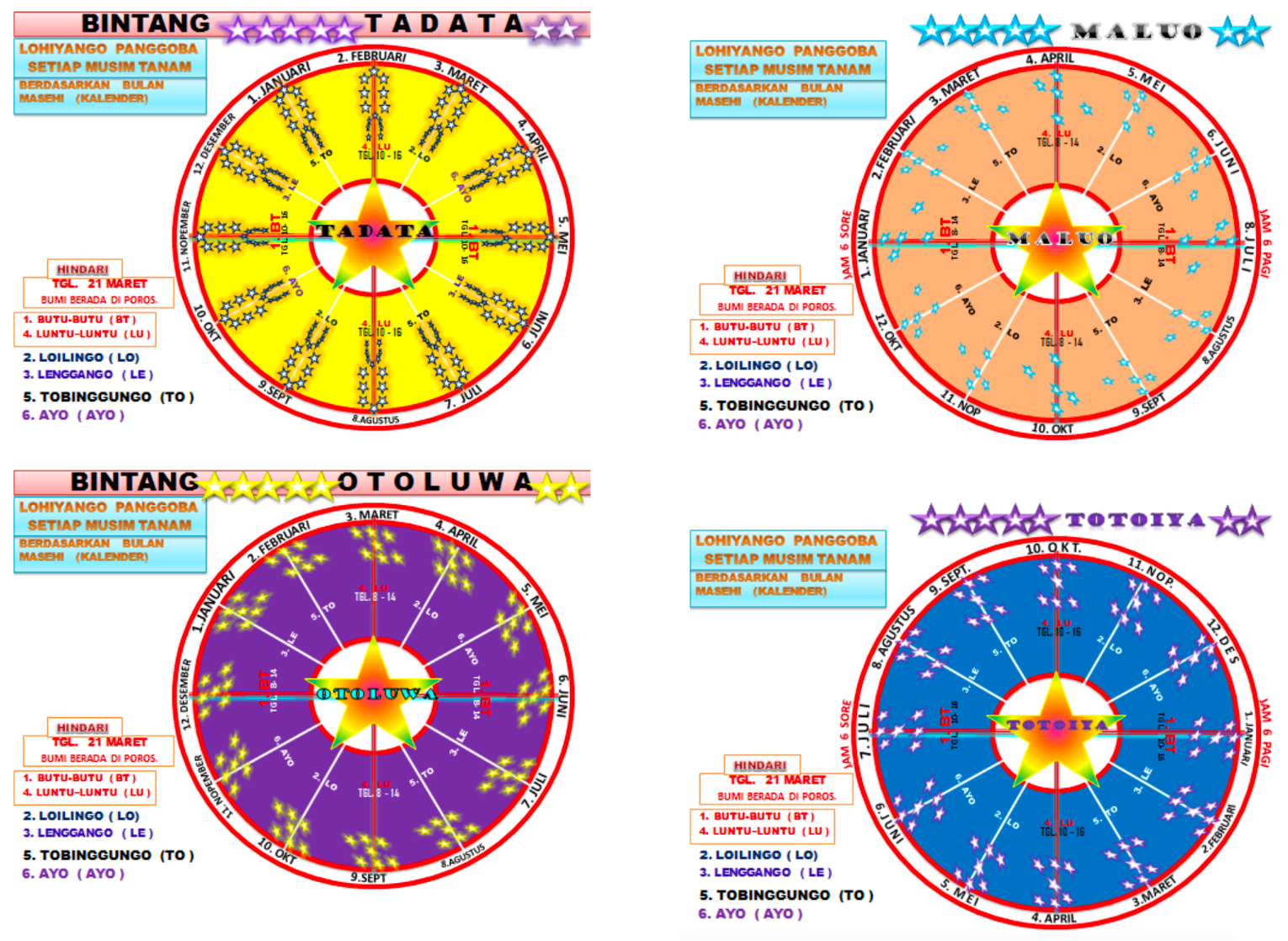

Driven by the Provincial Food Estate Program, Gorontalo’s agriculture has historically shifted from production of local foods for local consumption to market-oriented cash crops. More recently the environmental and social consequences of this transition have led some to argue for a shift to more sustainable agricultural techniques.

Although land and deforestation statistics are missing, estimates suggest that 82,370 ha of land is critically degraded while on 598 ha have been rehabilitated against a target of 7,094 ha specified in the previous five year plan (RENSTRA DLHK 2025-2029).

On a recent field visit, our team witnessed first hand the effects of the state-led transition to hybrid corn and chemically supported intensification.

Solutions in sustainable agroforestry

Our team at the Universitas Negeri Gorontalo have recently set up a Living Lab as part of their curriculum for agricultural training. It provides not only a context for training the students (most of whom are the children of corn farmers) but is also a facility for research and the demonstration of sustainable agroforestry techniques.

In our next phase of fieldwork the team in Gorontalo will be working with local communities to understand the impacts of Gorontalo’s agropolitan (food estate) program on local farmers and its implications for poverty, food security, climate and biodiversity.

They will also be working to build local capacity to implement climate resilient agroforestry systems and polyculture farming with the aim of improving livelihoods, food security and environmental outcomes.

East Kalimantan

Agriculture in East Kalimantan

East Kalimantan is currently the focus of efforts to transition from ‘brown’ to ‘green’ industries. In practice this means moving from coal mining to oil palm and forest conservation in exchange for carbon credits.

The expansion of oil palm and rice paddy marks a dramatic change in local livelihoods from shifting cultivation to permanent cultivation driven by state subsidies. However, the replacement of other food crops and forest with oil palm, puts increasing pressure on water resources and biodiversity.

The so-called ‘printing’ of rice paddy on lowland areas is supported by irrigation projects and accompanied by large-scale transmigration.

Lembo: climate resilient agriculture

Members of the LEAF Indonesia team visited a village in East Kalimantan where Lembo is still practised. The following video provides a ground level and aerial view of the landscape as it is shaped by Lembo.

Lembo isn’t just a form of agroforestry, but it is also a cultural practise involving collective rituals (e.g., adat harvest festivals) which reinforce sustainable harvest cycles and respect for the land.

However, the practice of Lembo is under threat due to the changing economics of agriculture which are influenced by the government’s Food Estates programs. Farmers are being encouraged to transition from the shifting agriculture of Lembo to permanent cultivation of palm oil while transmigration is deployed to increase areas of lowland rice, often on peatlands unsuited for rice cultivation. In both cases the consequences include soil degradation and increased vulnerability to climate-related hazards.

A sustainable model of Food Estate’s in East Kalimantan will need to adjust incentives to promote sustainable agroforestry and low-external input rice on the most appropriate land, avoiding peatlands unsuited to paddy rice.

West Papua

Agriculture in West Papua

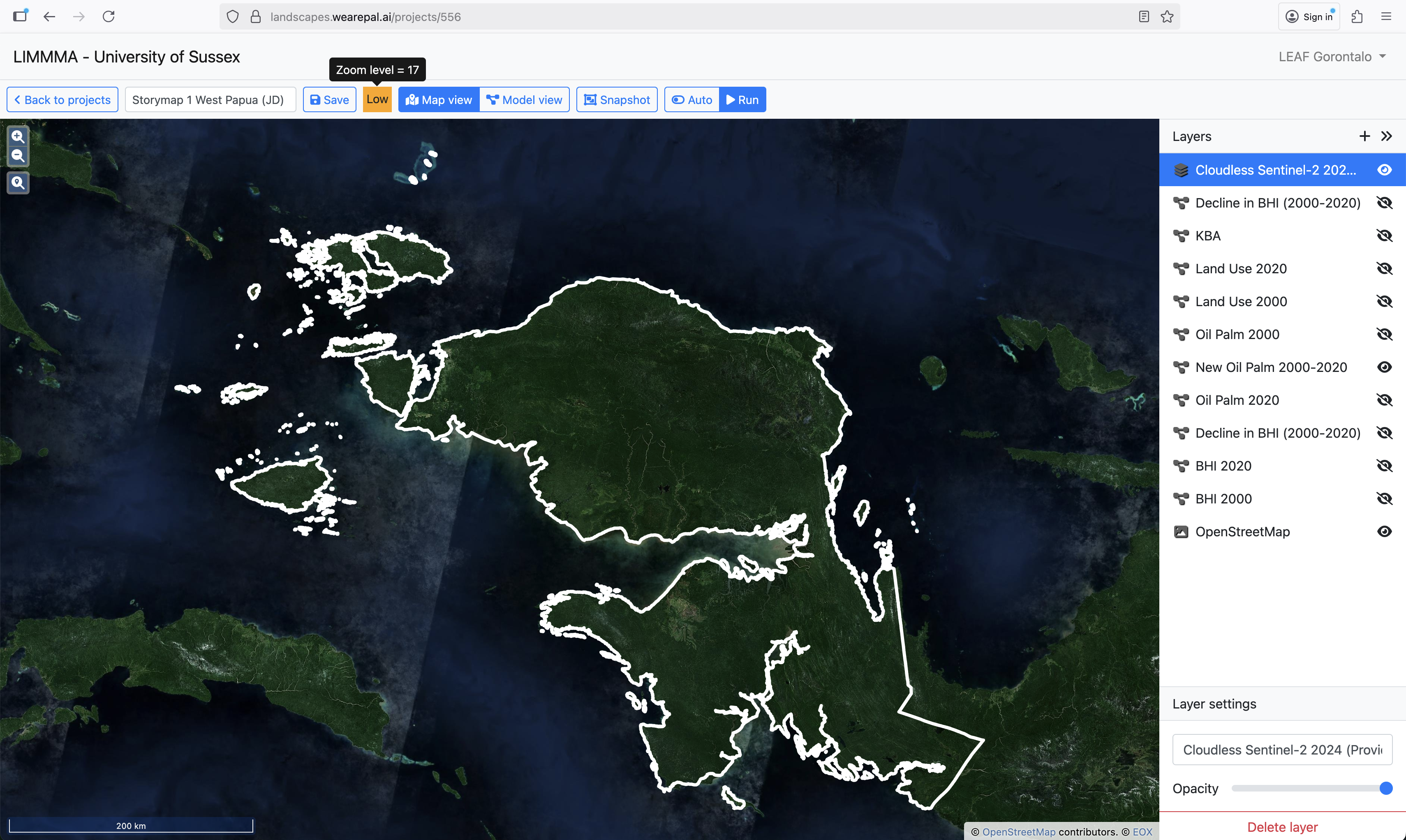

The scale of changes seen more clearly in close up using the slider to reveal the changes between 2000 and 2020. The following sliders show different parts of West Papua in close up.

Western

In the western part there are several large areas of oil palm appearing between 2000 and 2020.

Southern

And a similar situation in the southern part.

Eastern

While the eastern area sees a large-scale expansion of existing palm oil.

In addition to the environmental impacts of deforestation for oil palm, the conversion of forest to oil palm plantation often means encroaching on customary forest lands that have been owned, controlled and managed by indigenous Papuan communities through generations.

This has led to conflicts over land between indigenous communities and companies when land is converted without the consent of indigenous owners.

It also threatens the indigenous practise of sustainable agriculture, Sasi.

Sasi: traditional form of ecological management

Sasi is a form of local wisdom practised by indigenous communities in Papua serving as a customary legal institution to regulate the use of natural resources.

The essence of Sasi is the regulation of alternating periods of harvest or resource use with periods of prohibition (closed season) for land or marine resources.

It not only serves ecological functions but also contains rich social, cultural, legal and economic meanings.

Sasi helps to protect ecological resources while sustaining the supply of food and cash crops such as sago, nutmeg, coconut resin, as well as fish, clams, and sea cucumbers.

Not only does Sasi contribute directly to local food security, but it also forms a social contract which fosters cooperation and solidarity within communities and enhances their resilience.

Erosion of such locally adapted indigenous agroforestry and the cultural heritage which goes with is likely to lead negative impacts on local food security, biodiversity and livelihoods.

Conclusion

In each of the provinces our research teams are exploring in depth the implications of Food Estate Programmes for local communities and farmers. While agricultural livelihoods and the types of Food Estate interventions are different in each province, a common thread links them all.

Agriculture in each province is in the midst of transition from locally adapted indigenous practises to a modernisation of agriculture characterised by cash monocropping for export, supported by increasing dependence on external inputs.

While indigenous practises support local food security and ecological integrity, there is growing evidence that modernisation efforts are responsible for declining soil fertility and increasing vulnerability to climate related hazards which put local livelihoods and long term food security at local and national level at risk.

Our research seeks to highlight the multiple implications of contemporary Food Estate policies and support strategies for locally appropriate Food Estate models which contribute to local and national food security while protecting and recovering ecological resources, supporting rural livelihoods and contributing to climate goals.