1995 ‘One Million Hectare Peatland Development Project’, the ‘Central Kalimantan Mega Rice Project’ and the ‘Merauke Integrated Food and Energy Estate’ (MIFEE) which alone targeted 1.6 million hectares for food crops, energy crops and livestock in the 2010s.

One of the first of the new Food Estates to be announced was the ‘Delta Kayan Food Estate’ (DeKaFE) in North Kalimantan during 2011 (Lou et al. 2025, Setyo and Elly 2018, Galundra et al. 2010).

Sustainability Trade-offs

The suitability of land for different types of agricultural crop will be a critical factor in the productivity of Food Estates and food production needs to carefully balanced against the impacts of each land-use type on biodiversity.

The diversity and composition of species and the quality of habitats on and around cleared land will vary across the landscape so that some areas should be prioritized for conservation over others. For example areas of high biodiversity value and low potential for agricultural productivity.

High levels of carbon are sequestered and stored by forests and the implications for global and local climates of changes in forest cover will also have knock on effects on agricultural productivity and the risk of extreme weather related disasters.

Thus the impacts of Food Estates on biodiversity, climate and disaster risk must be traded-off against the benefits for food security and livelihoods.

Let us take a look at each of these issues in turn in our three case study provinces.

Land-use changes

- Policy on spatial plan, forest classifications,

- Land-use changes (spatial data: land expansion for food estate)

Biodiversity Trends

Indonesia is one of the world’s largest and most biodiverse countries. It contains 10% of the world’s flowering plant species, 12% of its mammals, 16% of its reptiles and 17% of its birds. Among these, the species threatened by extinction are 63 mammals, 21 reptiles, and 140 birds (CBD Secretariat 2016).

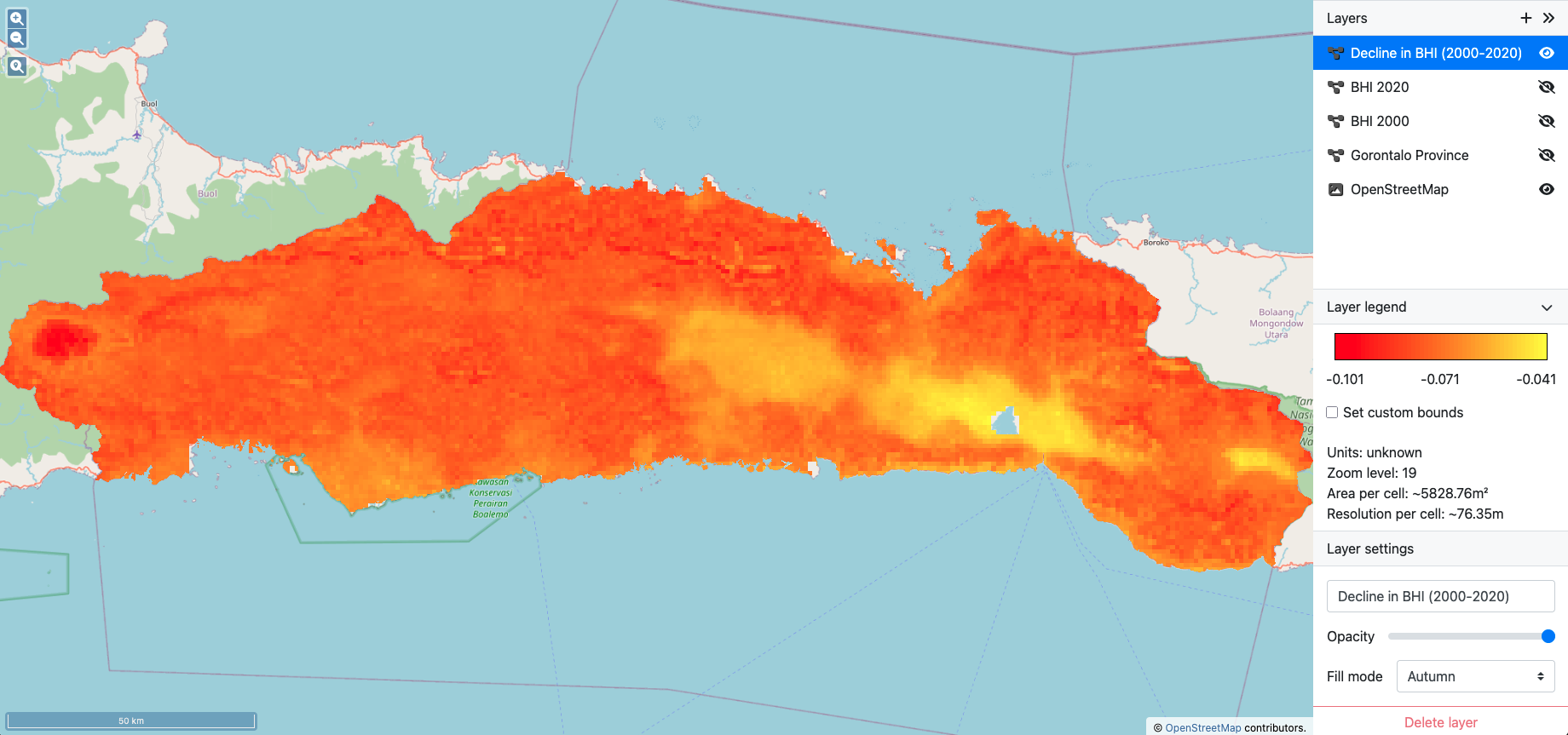

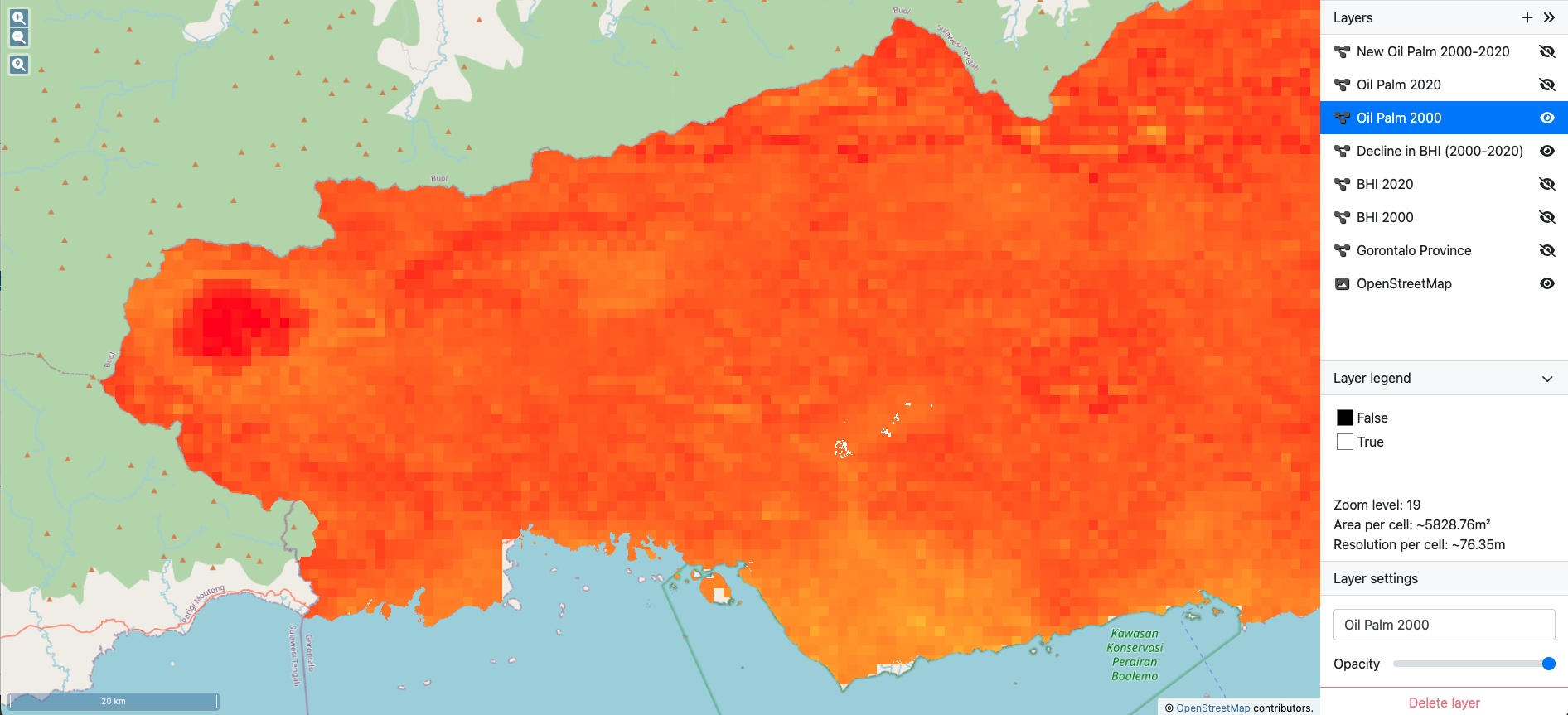

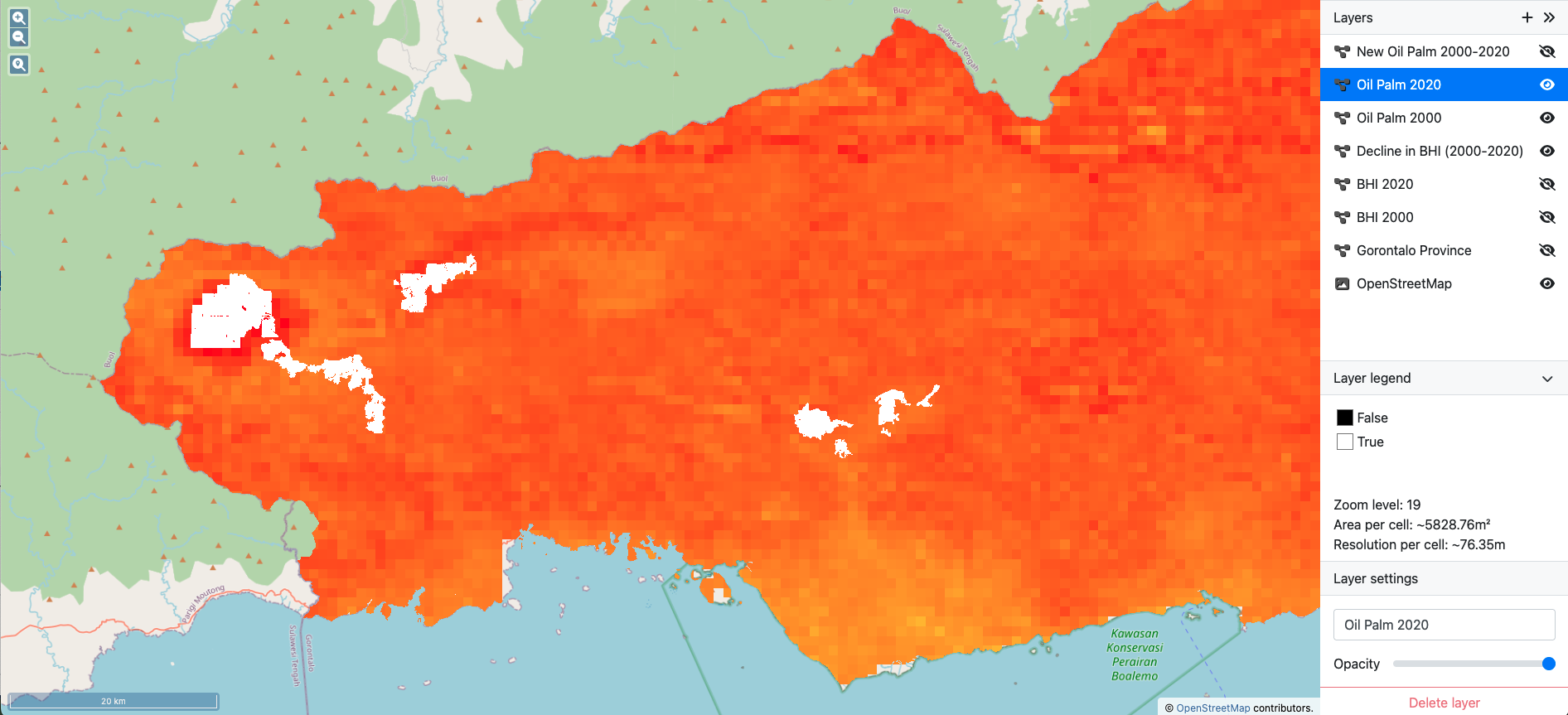

So how might Food Estates influence biodiversity in our three case study provinces?

Let’s see how forest clearance for Palm Oil Plantations impacts biodiversity.

Among the multiple causes of these localized declines in biodiversity we have good evidence of the specific impacts of the clearance, fragmentation and degradation of forests.

While the loss of habitat has the most obvious impact on forest species, there are also ripple effects on biodiversity which extend through space and time.

Forest clearance and infrastructure reduce the connectivity of habitats on the fringes of forests, reducing the available habitat for many animal species. This can lead to ‘empty forest syndrome’ in which areas of forest become devoid of large vertebrates. This in turn, interrupts seed-dispersal, especially for large-seeded trees, leading to increased clustering of seedlings which reduces seedling survival and hinders the recovery of damaged or selectively logged forests and also changes the composition of regrowth forest on abandoned agricultural lands. Over the long-term this will shift forest margins towards lower density trees whose wind-dispersed seeds reach more widely and will eventually reduce the overall carbon stock density. (Lewis, Edwards, and Galbraith 2015) .

Degradation of forests also contributes to increased risk of wildfire. While natural fires in humid tropical forests are extremely rare, logging and fragmentation increase fuel loads, create warmer, drier conditions and multiply ignition sources leading to increased instances of fires. In the aftermath of fires primary birds are replaced by non-forest species, repeat burning risk increases and eventually the forest can shift to savanna type vegetation with permanent loss of species and ecosystem functions relative to forest habitats (Lewis, Edwards, and Galbraith 2015).

Not only do these impacts have significant implications for long-term biodiversity trends but they also contribute to increases in carbon emissions.

- Crops, plantations, birds

Carbon emissions and storage trends

Global and local climates are facing increasing pressure as a result of decades of land-use change.

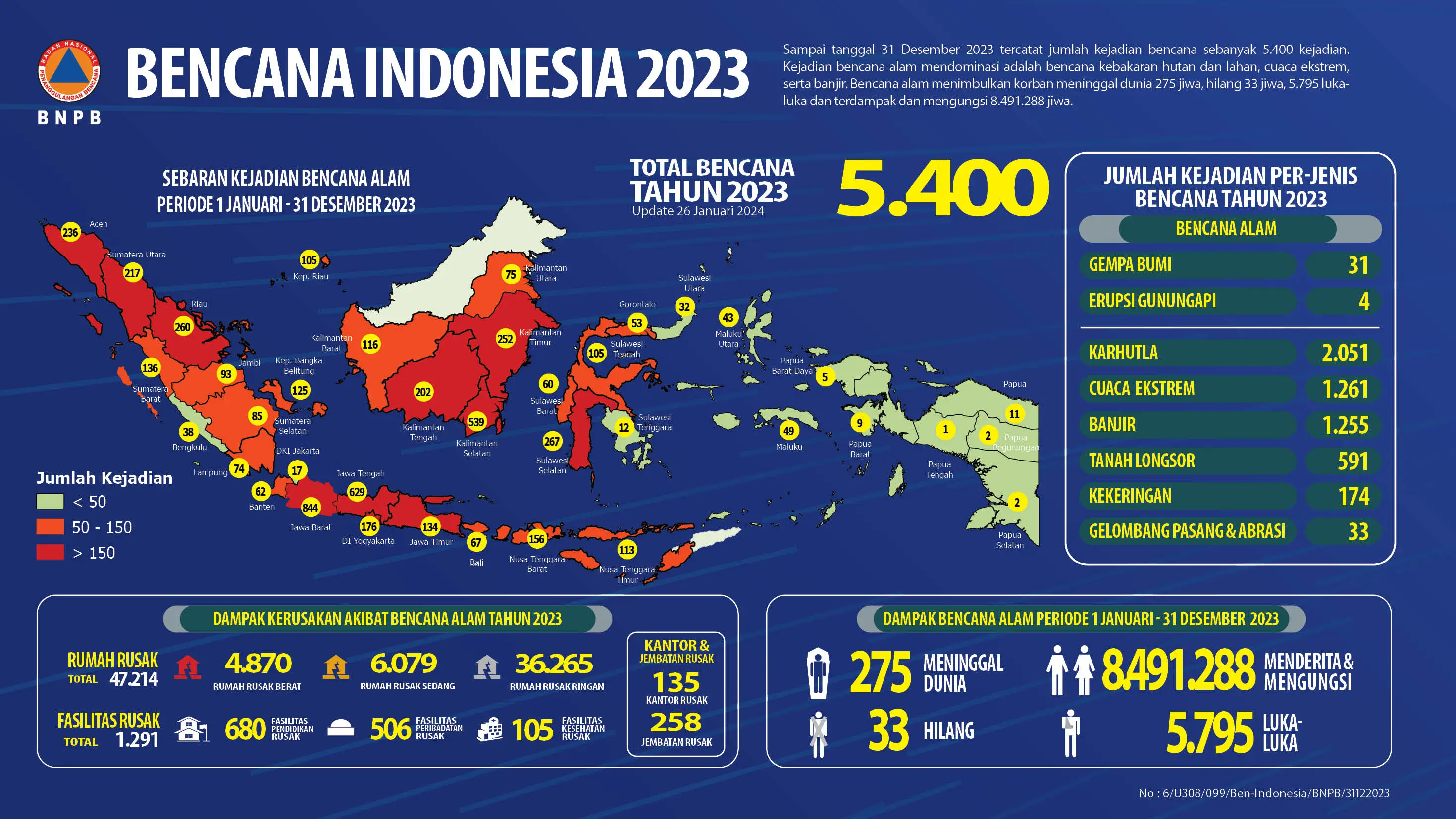

As deforestation drives GHG emissions, biodiversity loss, worsens wild fires and contributes to changes in local climatic conditions, the risk of disasters related to extreme weather also increase.

- Deforestation, forest fire, pollution

Disasters

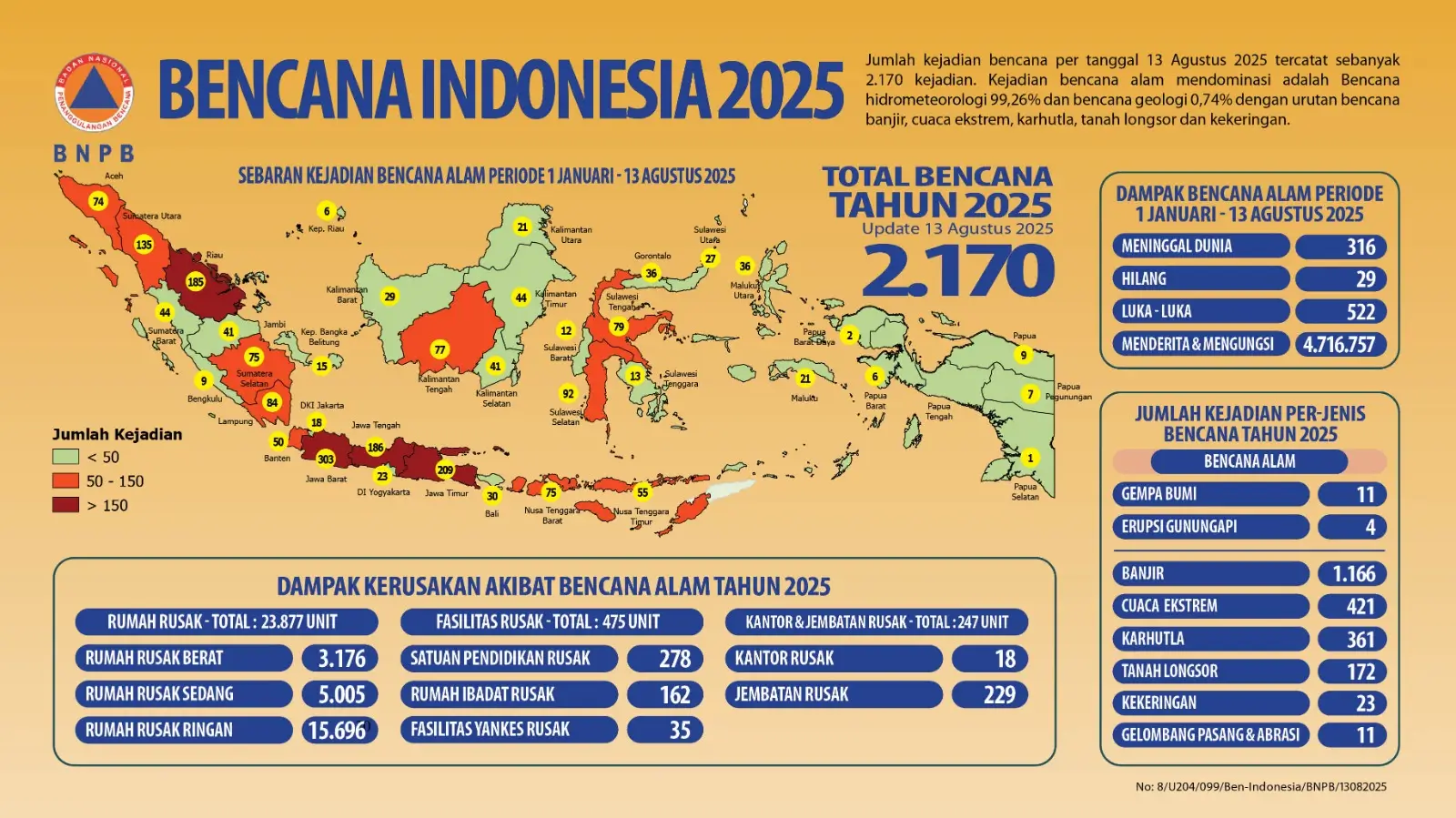

The National Disaster Management Agency (Badan Nasional Penanggulangan Bencana) reports an increase in annual incidences of weather related disasters (flooding, landslides, forest fires) from 928 in 2008 to 4,650 in 2020.

- Landslide, flooding, drought, forest fire

Implementation Scenarios

Understanding the drivers and impacts of these changes is therefore crucial if the Food Estate Program is to be implemented in a way that balances the goals of food security, biodiversity and climate change mitigation while improving the livelihoods of those directly implicated in the process.

Depending on how Food Estates are implemented these multiple trade-offs will unfold in different ways. Our project takes deeper dives into three provinces to understand the implications of different implementation scenarios (through surveys, interviews, and mapping geospatial data).

Looking in more detail through we can learn more about the relationship between these various impacts on biodiversity and climate as well as the implications for farmer’s livelihoods and the ES on which they depend (e.g. agroecologial agroforestry in Gorontalo).

That understanding must be based on adequate data and communicated in a compelling way to all the stakeholders involved in designing and implementing the Food Estate Program. In addition to the three case studies, our team have been working on a bespoke platform to make accessible a range of public datasets for analysis and visualization to support such an evidence-based understanding of the potential implications of this radical policy.